For many visitors to London, the King’s Road in Chelsea is synonymous with the delights of shopping. These days, it’s not unlike most other shopping streets, if a bit more upscale. However, from the 1960s to the 1980s, it really was THE place to shop in London. I’ll be looking at three important, but very different, designers from the last 60 years who started their careers in Chelsea and whose fashion influence is still felt today.

First, some history:

The Chelsea of today – with its expensive properties and wealthy, cosmopolitan residents – is very different from its roots as a small fishing village by the Thames in southwest London. In the 16th century, Sir Thomas More, King Henry VIII’s Lord Chamberlain, lived there in some splendour. Henry VIII himself had a manor house, called Chelsea Place, on the site of 19-26 Cheyne Walk. It was later home to his daughter, who went on to become Queen Elizabeth 1, and two of his famous six wives! Well over a century later, King Charles II built the Royal Hospital further east of Chelsea Place for injured soldiers.

By the 18th century, a settlement had sprung up along the main carriage route taking Londoners out to Richmond and Hampton Court Palace – the “Royal Way” or “The King’s Road,” as it became known. Sir Hans Sloane, whom Chelsea’s Sloane Square is named for, bought Chelsea Place in 1717. When he died, charming houses were built on the site. Very little of the Tudor manor survives, apart from some remnants in the rear gardens of Cheyne Walk properties.

18th-century houses in Cheyne Walk, fronting the River Thames, the site of Henry VIII’S manor house. Photo Credit: © Clare McCoy.

18th-century houses in Cheyne Walk, fronting the River Thames, the site of Henry VIII’S manor house. Photo Credit: © Clare McCoy.

Through the following centuries, Chelsea became fertile ground for creative types, hosting artists such as JMW Turner and James Whistler, and writers including Dracula creator Bram Stoker and the playwright Oscar Wilde. In the1920s, the bright young things, bored with Mayfair, formed a bohemian haven in Chelsea, helped by the presence of the Chelsea Arts Club (on Old Church Street) and Chelsea College of Arts (now part of the University of the Arts).

From the 1950s to the 1970s, there was nowhere in London – apart from Soho – that could rival Chelsea for cutting-edge fashion. British fashion is unique because of our love of eccentricity, our irreverent, energetic street style, and our designers’ ability to express individuality and challenge the status quo. Chelsea, in particular, has always had a slightly alternative vibe. Geographically, it feels marooned from the rest of London. It is only served by one tube station (at Sloane Square), and the River Thames acts like a physical and psychological barrier, all of which has seemed to protect Chelsea’s distinct “otherness”.

Albert Bridge and on into Chelsea, from Battersea Park. Photo Credit: © Clare McCoy.

Albert Bridge and on into Chelsea, from Battersea Park. Photo Credit: © Clare McCoy.

Mary Quant: “Quaint…she ayn’t”

It’s difficult for us to imagine what it was like for a young person to shop in the 1950s. Teenagers were expected to look like miniature versions of their parents. In post-war Britain, people dressed according to established class hierarchies. Fashion changed comparatively slowly, and clothes were meant to last. They were often made for you, if you could afford it, with dressmakers coming to your house. Most clothes shops were rather intimidating places. Clothes were neatly folded or hung well away from customers. They were called “Madam shops,” where all customers were called “madam”. There were teams of snooty assistants wielding tape measures, and supercilious models stalked the aisles in matching hats, gloves and shoes.

All that changed in 1955. Mary Quant opened her shop Bazaar at 138a King’s Road when clothes and fabric rationing came to an end. After finishing her illustration and art education at Goldsmiths, Mary had worked for an haute couture milliner in Mayfair – designing hats for the elite to wear at high-society events like Ascot. She went into business wanting to design for everybody – to make fashion “more approachable, less intimidating and more fun…clothes to be young and alive in”. Her shop even had a cafe in the basement. Soon, anyone who was anyone flocked to Bazaar, not just to shop, but also to load up on the free drinks, hear the latest music, and see and be seen (and photographed!) before going nightclubbing.

No. 138, Kings Road in Chelsea. Photo Credit: © Clare McCoy.

No. 138, Kings Road in Chelsea. Photo Credit: © Clare McCoy.

Quant was a self-taught fashion designer and had great business acumen, but in the beginning, Bizarre was run like a cottage industry. The profits from one day paid for the material for the clothes displayed next. This meant that Quant had just a few hours to produce short runs of unique looks that needed to sell well. And sell she did! After the catastrophic losses of World War II, the Baby Boomers were coming of age in the 1960s. It’s estimated that 35% of London’s population was under 25. And real earnings rose by 70% from 1945-1965, creating what we now call the Youth Market. What’s more, the passage of the Equal Pay Act gave women more financial independence, whilst the availability of the contraceptive pill offered them social and sexual freedoms. All of this created a perfect retail storm, and the “Street style of the Chelsea Modern” became the new haute couture!

Quant’s clothes were simple and practical, with clean lines. They were boyish, free-spirited and relatively cheap to make. She used modern, washable textiles – PVC, nylon, stretch rayon – printed with blocks of colour, stripes or circles. This geometry was greatly influenced by both the Pop Art and the Op Art movements. It helped that she looked like a model herself; Quant had a strong, angular face and big, heavy-lidded eyes. Her “geometric bob” haircut – a huge contrast to the overly elaborate “beehives” – launched the career of Vidal Sassoon. Quant modelled her own designs with coloured and patterned tights that matched her outfits, an innovative idea at the time. The “mini” started because she wanted to “run for the bus!” The idea for miniskirts and dresses may not have been original, but it was Quant who made them ubiquitous on the streets, and she named them after her favourite car – the Morris Mini!

In the ‘80s, Quant moved into bedlinen, paint and wallpaper. At age 90, she continues with her makeup range. A hugely successful retrospective in 2019 at the Victoria and Albert Museum celebrated her legacy.

Mary Quant in December 1966. Photo Credit: © Jac. de Nijs / Anefo via Wikimedia Commons.

Mary Quant in December 1966. Photo Credit: © Jac. de Nijs / Anefo via Wikimedia Commons.

Ossie Clark: The King of the King’s Road

The style muses of the ‘60s were “ordinary” people like Twiggy, Jean Shrimpton and Julie Christie who didn’t speak with upper-class accents, as well as pop stars (the Stones, the Beatles, the Kinks) and television personalities of new youth-oriented shows like Top of the Pops and Ready Steady Go!

But by the late 1960s, a different vibe was flowing around the streets of Chelsea – a yearning for the decadent but feminine style of the 1930s. In fact, it was the actress Marlene Dietrich who was the greatest influence on a young Northern designer called Raymond “Ossie” Clark. After getting his postgraduate degree from the Royal College of Art in 1965, he got a big spread in the August Issue of British Vogue the same year, aged just 23. In 1966, he started working at fellow designer Alice Pollack’s Quorum boutique on Radnor Walk off the King’s Road, and by 1974 he was designing under the Radley label.

Ossie had a very eventful life. He divorced his great friend Celia Birtwell after just four years of marriage (1969 to 1973) and died 30 years later, alone and penniless in a council flat, murdered by his lover. His confused sexuality and drug use had contributed to his downfall.

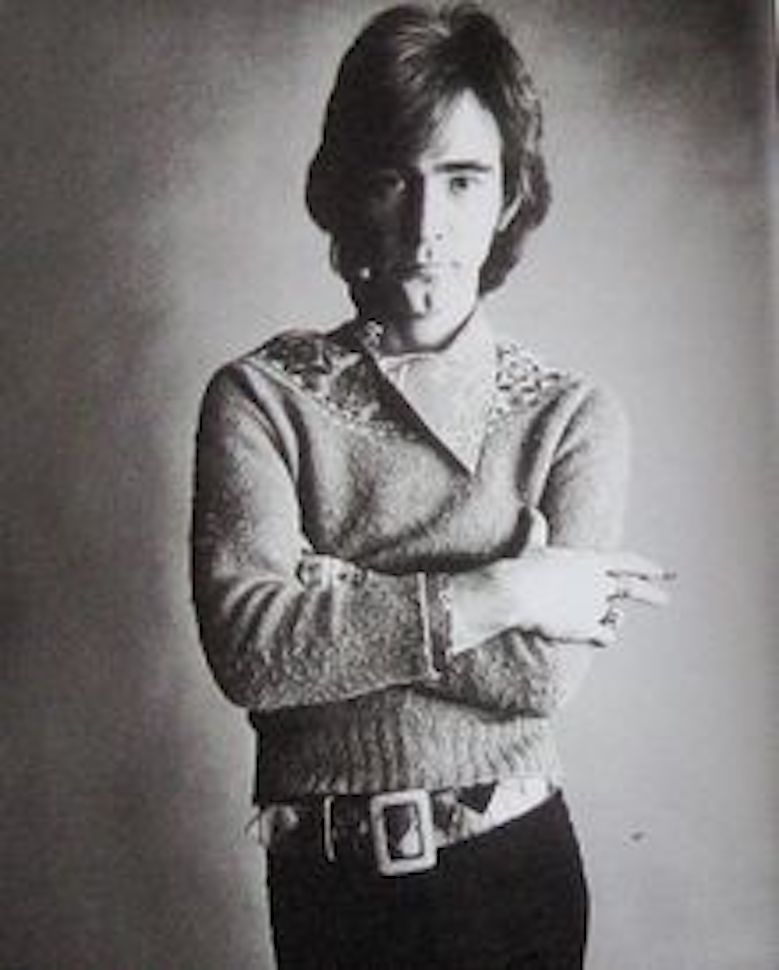

Raymond Ossie Clark, English Fashion Designer. Photo Credit: © Wikimedia Commons.

Raymond Ossie Clark, English Fashion Designer. Photo Credit: © Wikimedia Commons.

Clark had started out making clothes for his much older sisters and their children, designing a swimming costume for one of them when he was just 10! He studied at the Regional College of Art in Manchester, where he met David Hockney and Celia, who became a talented textile designer in her own right. He went to New York and was inspired by the hedonistic scene of Andy Warhol and “the Factory”. Celia and Ossie are immortalised in a 1971 painting by Hockney titled Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy, which is in Tate Britain.

His first solo fashion show was at Chelsea Town Hall in 1967, right in the middle of the King’s Road, showing BAME (Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic) models on the catwalk for the first time. Clark, in partnership with Birtwell, created his own fashion label for the Quorum boutique, and so started the most famous British fashion collaborations of the 20th century. Birtwell’s textile designs matched the zeitgeist of the time. They evolved from fluorescent colours and bold stripes to Art Deco-inspired shapes, and dreamlike surrealism with a touch of romanticism.

Ossie put her prints on opulent, expensive fabrics that draped and flowed beautifully around the body – moss crepe, crepe de chine, diaphanous chiffon, silk satin – a contrast to Quant’s penchant for polyester. Clark didn’t need a pattern to cut into the fabric; he was able to translate three-dimensional ideas onto flat surfaces almost instantaneously. This is a rare skill, and it can be seen in the “architectural” quality of his designs. He often cut “on the bias”, resulting in a sexy, clingy movement to outfits. His signature style featured curved lapels, halter necks, keyhole-shaped necklines, trumpet-shaped sleeves and side-split maxi skirts. Unlike Quant, he hated zips and used buttons covered in material instead.

In his heyday, Ossie’s clothes were worn by the likes of Faye Dunaway, Brigitte Bardot, Peter Gabriel, Liza Minnelli, and Bianca and Mick Jagger (the red and black cape worn by Mick at the notorious Altamont Festival in 1969, for example). But in the Punk era of the mid-1970s, everyone was rebelling against his retro, whimsical style. He was also hopeless with finances. His work is in the permanent collection at the V&A. Clark is still highly collectable, and many in the fashion world cite him as a major influence.

Ossie Clark satin and chiffon trouser suit in Botticelli print, 1969. Photo Credit: © Mabalu via Wikimedia Commons.

Ossie Clark satin and chiffon trouser suit in Botticelli print, 1969. Photo Credit: © Mabalu via Wikimedia Commons.

Vivienne Westwood, the High Priestess of Punk

The 1970s were marked by nervous tension, scepticism and discontent, with developments including the Arab/Israeli conflict, the UK miners’ strike and sectarian violence in Northern Ireland that spilled over into UK cities. Gloom descended with a double whammy of high inflation and unemployment. By the middle of the decade, the bohemian dreamers of Chelsea had been pushed west to the World’s End – a suitable name for what was seen as the “wrong” end of the King’s Road.

Named after the 19th-century World’s End pub (see photo above) that still exists, this end of Chelsea had been a hippy hangout in the ‘60s, with tea and magic mushrooms sold at Gandalf’s Garden near the pub and vintage nostalgia purchased at Granny Takes a Trip at No. 433. Nearby, at 430 King’s Road, Vivienne Westwood and her boyfriend, ex-film student Malcolm McLaren, opened Let It Rock in 1971 (later renamed Too Fast to Live, Too Young to Die), selling original 1950s clothing – “Teddy boy” jackets and thick crepe-soled shoes called “Brothel Creepers”. This was a shocking contrast to the floaty romanticism of the hippy ideal.

The World’s End Pub in London. Photo Credit: © Clare McCoy.

The World’s End Pub in London. Photo Credit: © Clare McCoy.

For those of you unfamiliar with Teddy Boys, I’ll explain. In the 1950s, rebellion against post-war austerity in Britain had spawned a subculture of urban working-class gangs. The two main ones were the so-called Mods, with their Italian suits and polo shirts, and the Teddy Boys, who preferred long, draped jackets with velvet lapels, straight drainpipe trousers, brocade waistcoats, shoestring bow ties and the above-mentioned shoes. This look was a parody of the Edwardian gentleman 40 years before – hence the name Teddy or Ted.

In their World’s End shop, Westwood and McLaren were tapping into more than just a bit of retro, working-class nostalgia. They were tuning into a pervasive malaise, a general resentment and cynicism, an anger against the failure of modernism. Modernism had given the world rationality, rules of logic and a faith in an objective reality that could be measured and quantified. As a philosophy, it proposed that science could be applied to produce continuous economic and social progress. But judging by the economic failures of the 1970s, it hadn’t! However, the theory of postmodernism provided an alternative: cultural pluralism. This concept suggests we are all defined by our own views of the world, and that inspiration is in a constant state of flux. Ideas can come from anywhere and anything, and there are no absolute truths, only interpretations.

The World’s End shop showing its famous clock with backward spinning hands. Photo Credit: © Clare McCoy.

The World’s End shop showing its famous clock with backward spinning hands. Photo Credit: © Clare McCoy.

Postmodern philosophy poses the idea that we are all confined by economic and social structures that we may not be aware of. Society needs to examine these structures and “deconstruct“ them. The theory of deconstructivism as applied to fashion (and to art and architecture) proposes that the choices we make when we decide what to wear (or to create) send out “signals“ to others. To understand these signals, we need to strip the creative process down to its bare bones and then start again, showing the workings of our minds. This can be summarised by saying that anyone can have a go at creating; there is no right or wrong way as long as you express yourself. The Punk Rock movement in music is an example of “doing it yourself”.

From 1976, we have our second famous fashion collaboration starting in Chelsea, with McLaren providing the hype and the punk bands and Westwood doing the “look”. Their shop became “ground zero” of a music and fashion revolution! Westwood’s designs were worn by the Sex Pistols on tour, and both music and fashion fused to create a British fashion moment. Their shop changed its name to Sex, selling subversive rubberwear “for the office” and then it became Seditionaries, offering what Westwood called “motifs of rebellion”.

Vivienne Westwood at King’s College London in 2008. Photo Credit: © FormerBBC via Wikimedia Commons.

Vivienne Westwood at King’s College London in 2008. Photo Credit: © FormerBBC via Wikimedia Commons.

Her ripped T-shirts covered with exposed seams, challenging slogans and safety pins were pioneering deconstructivism. Her bondage trousers certainly looked fetishist, but they also acknowledged Britain’s traditional military heritage. The unfashionable end of the King’s Road became a mecca for young, disillusioned teenagers from the suburbs. Ironically, the young punks couldn’t afford her designs, but they were easily replicated because anyone could have a go at making them.

Since she left McLaren and went solo in 1982, Westwood’s creativity has remained true to her punk roots. Her views of cultural pluralism launched the “New Romantic” look, and the music of Culture Club, Depeche Mode and Spandau Ballet followed. She became a meticulous researcher in London’s Wallace Collection and the V&A, unashamedly raiding the past. She produced the “Mini Crini” in 1985, an audacious parody on the crinoline, the 1960s miniskirt and the typical British royal style of twinsets and pearls.

Her clothing shows a strong respect for traditional British tailoring and the French sense of design and proportion. In fact, she said that “The British and the French invented fashion, and there has been this creative tension ever since. The Parisians have style, but there really is nowhere quite like London.”

Vivienne Westwood Mini Crini. Photo Credit: © Woehning via Wikimedia Commons.

Vivienne Westwood Mini Crini. Photo Credit: © Woehning via Wikimedia Commons.

Westwood was born into a working-class family used to the idea of “make do and mend”. She was a primary school teacher in London until she was 30, and apart from a course in jewellery making, had no formal design training. Despite that, she was three times voted British Designer of the Year, the last time in 2006, and was made a Dame of the British Empire (a CBE) by the Queen in 2006, famously showing her bare bottom to the adoring press outside Buckingham Palace, wearing her “Anglomania” fusion range! Her clothes shock, irritate and provoke and – she hopes – they inspire change. Westwood now uses her fashion brand as a platform to express her views on ecology, human rights and nuclear disarmament. The irony of the fact that the fashion industry is one of the most polluting in the world is not lost on her – but she advises to “choose well, buy well…make it last…everyone is buying too many clothes!”

Leave a Reply