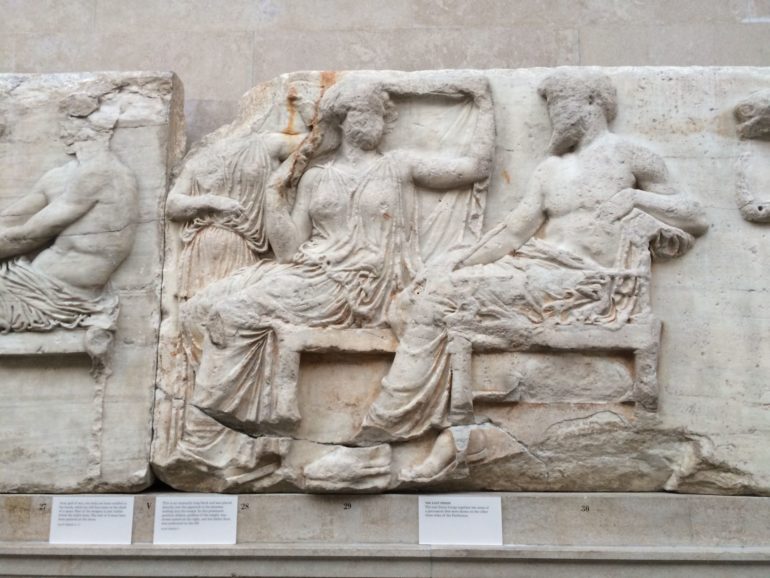

The year 2017 marks the bicentenary of the exhibition of the Parthenon Marbles at the British Museum. The artefacts were removed from the Athenian Acropolis in 1801 and 1802 by Thomas Bruce, seventh Lord Elgin British Ambassador (1799–1803) to the Ottoman Empire. The sculptures were commissioned in the fifth century BC as part of the rebuilding of the City of Athens ordered by the statesman Pericles following the successful war against the Persians. To fund their creation, Pericles used money entrusted to Athens by the Greek city states of the Delian League. Athens could thus be seen to be pushing the message that it was the new power to be reckoned with rather than the fading Achaemenid Empire.

Such a statement would not have been lost on Lord Elgin at the time of the fight between the two great colonial powers of the day, Great Britain and France. Indeed, Lord Elgin in his correspondence with his overseer Giovanni Battista Lucieri expressed his anxiety that the French might get to the marbles before him. This argument was used during the hearings of the 1816 Select Committee of the House of Commons as justification for Elgin’s actions and as reason for their purchase for the British Museum – for £35,000 instead of the £73,600 originally requested by the by now bankrupt Lord.

The presence of the marbles at the British Museum was linked with the aesthetics of British society and considered material proof that Great Britain was the dominant colonial power and the embodiment of the Ancient Greek spirit. According to Ian Jenkins (Archaeologist and Aesthetes, 1992) the possession of the marbles defined the British aesthetic and cultural victory after the battle of Waterloo, the equivalent of the battle of Marathon.

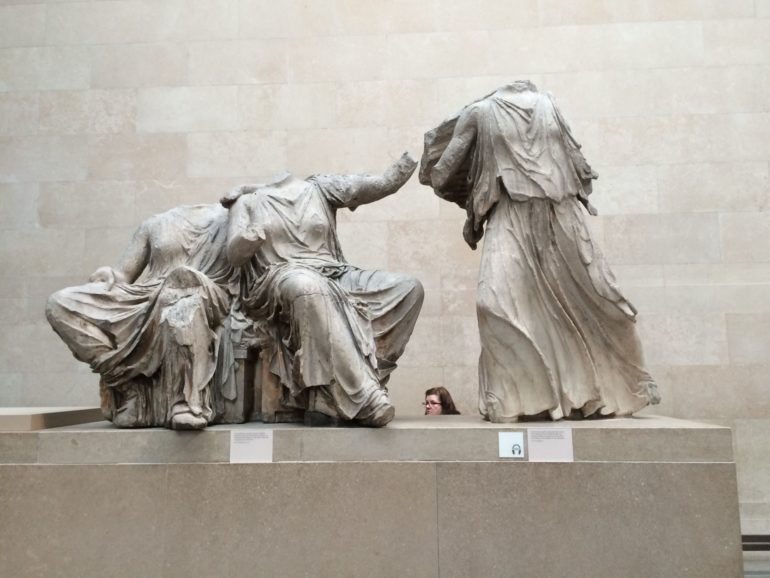

For the Greek nation the absence of the marbles from the city that conceived and executed them, has been seen as theft, bereavement and even as the imprisonment of children by a foreign power. British travellers of the nineteenth century record folklore stories where the Karyatids were heard crying in the night for their kidnapped “sister”. Discussion on the return of the marbles started almost as soon as Greece became a sovereign nation, but the first official Greek government request dates only from 1982.

In the 200 years since they first went on display, the marbles have been the mythical Apple of Discord between the British Museum and the Greek state. Arguments for the sculptures’ return have shifted with the times. Greece, with the creation of the impressive new Acropolis Museum, is no longer the poor relative that needs to prove its ability to look after what is hailed as the cultural heritage of the Western world. The British Museum, following the scandal of the cleaning of the marbles ordered by Lord Duveen in the 1930s and which came to light in the 1990s, has recently asserted its position as the guardian of the artefacts by redefining itself as the Museum of the World, for the World.

The seizure of the sculptures, built by one empire to show its might, taken by another for the same reason, reminds us that empires rise and fall. I am under no illusion that the Parthenon Marbles issue will be resolved in the near future. As a Greek, an archaeologist and a Blue Badge Tourist Guide living and working in London, entering the Parthenon galleries is special. It is a piece of home in my adopted home, a reminder that it is the myths of Athena, of Centaurs, of the Olympian Gods, first heard when I was only a child, that morphed me into who I am today. And I do believe that in order to fully understand and appreciate these magnificent works of art they should be seen not in separate locations but in their entirety.

Leave a Reply