The art-loving and generous founder of the Tate, sugar magnate Henry Tate, collected contemporary British art. He knew what he liked; pictures (some say sentimental) that told a story, animal subjects, and landscapes. He bought works by Millais, Stanhope Forbes, and Luke Fildes, displayed in his own gallery at Park Hill. However, intellectuals sneered at his taste. Resolved to found a public gallery of British art with his own pictures, the gallery finally opened in 1897. His pictures are still there, now joined by numerous masterpieces from every century, including the 21st. A tour of Tate Britain with a Blue Badge Tourist Guide of some key works at Tate Britain is not only crucial in order to capture and enjoy the essence of British art through the ages, it also helps to situate the ‘national’ output in a European context of mutually evolving exchange and inspiration.

HOLBEIN’S INFLUENCE – A Man in a Black Cap by John Bettes

Currently the earliest work (see inscription ‘ANNO D [OMIN] I 1545’ on the front) in the Tate collection, this striking portrait is significant because the artist’s name – John Bettes – is recorded on the back which is very rare on British paintings of this period. The work resembles that of Hans Holbein the Younger, the great German court painter of Henry VIII. Did Bettes work for him? The brownish background was originally a deep blue – a hue often used by Holbein for his backgrounds. Bettes, however, used ‘smalt’ as pigment, which tends to change colour irreversibly to brown or grey under the effect of light. To the artist – no doubt unaware of this – smalt must have seemed a godsend: the rich blue of ultramarine at a fraction of the cost! Apart from the superb draughtsmanship and masterly brushwork, this portrait would have been a splendid compilation of sumptuous colours and textures, making the sitter very pleased.

EMERGING BRITISH ARTISTS – A Scene from ‘The Beggar’s Opera’ VI by William Hogarth

This is one of the first paintings of an English stage performance. It represents a climactic scene from John Gay’s popular The Beggar’s Opera, first performed in 1728. Hogarth has included members of the audience, notably at the far right, the Duke of Bolton, the real-life lover of Lavinia Fenton, the actress playing the part of Polly Peachum. An unforeseen and scandalous aspect of the production was the fact that the Duke, twenty-three years her senior and separated from his wife, fell in love with Lavinia on the opening night and then attended every performances. At the end of the season, Miss Fenton retired to become his mistress, and on the death of his wife, the Duchess of Bolton. Although his style was influenced by French rococo artists, Hogarth was both a realist and social critic and marked the end of the long dominance of Dutch and Flemish painters in England and the beginning of a native school.

Tate Britain: A Scene from ‘The Beggar’s Opera’ VI by William Hogarth 1731. Photo Credit: © Ingrid Wallenborg.

Tate Britain: A Scene from ‘The Beggar’s Opera’ VI by William Hogarth 1731. Photo Credit: © Ingrid Wallenborg.

THE ‘GRAND STYLE’ – The Death of Major Peirson, 6 January 1781 by John Singleton Copley

Although initially used to describe paintings with subjects drawn from ancient Greek and Roman history, classical mythology, and the Bible, at the end of the 18th century’ history painting’ included modern historical subjects such as battle scenes. The style considered appropriate for such motifs was known as the ‘grand style’. Copley, an American artist, earned huge success and great wealth from history paintings such as this patriotic and dramatic picture which shows the untimely death of an English officer killed by French invaders in Jersey. The figure wearing the rather flamboyant uniform of the Royal Ethiopian Regiment is sometimes referred to as Pompey, Major Peirson’s black servant. The Royal Ethiopian Regiment was made up of Black Loyalists, former or escaped slaves, who joined British colonial forces during the American Revolutionary War. However, they never actually served in Jersey. Never mind, it makes Pompey look fabulous!

Tate Britain: Detail from The Death of Major Peirson 6 January 1781 by John Singleton Copley 1783. Photo Credit: © Ingrid Wallenborg.

Tate Britain: Detail from The Death of Major Peirson 6 January 1781 by John Singleton Copley 1783. Photo Credit: © Ingrid Wallenborg.

‘NATURAL’ LANDSCAPES – Flatford Mill by John Constable

The scene is a rural idyll with a typical Constable dash of earthy realism. The beloved landscape around his birthplace at East Bergholt, Suffolk provided the artist with inspiration all his life. He never travelled abroad and remained intensely patriotic throughout his life. If he were alive today, he would probably support BREXIT. However, ‘Flatford Mill’ attracted little notice at the 1817 Royal Academy exhibition in London and failed to sell. Constable completed his works in the studio using preliminary oil sketches he did on the spot to capture the reality of nature. At the time this was a revolutionary process that moved landscape painting on from the allegorical and romanticised to the naturalistic, eventually inspiring artists of French ‘Impressionism’. In 1824 his landscape paintings met with real success at the French Salon and were admired by Eugène Delacroix. In fact, such was the success that the French king, Charles X, awarded Constable a gold medal. Given that he considered the French “the enemy,” Constable refused to travel to Paris to receive it.

Tate Britain: Flatford Mill by John Constable 1816 – 17. Photo Credit: © Ingrid Wallenborg.

Tate Britain: Flatford Mill by John Constable 1816 – 17. Photo Credit: © Ingrid Wallenborg.

PRE-RAPHAELITES – Ophelia by John Everett Millais

This luminous picture, which represents the death of Ophelia from Shakespeare’s Hamlet, was painted by a member of the influential Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. The Pre-Raphaelites were a secret society of young artists founded in 1848. They were opposed to the Royal Academy’s teaching of the ideal as exemplified in art by the Renaissance master Raphael. They believed in an art of serious subjects treated with maximum realism, and Tate Britain has many masterpieces of Holman Hunt, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and Millais, who were the principal founder members. Ophelia was part of the original collection of Henry Tate’s paintings. When first exhibited in the mid-19th century, Pre-Raphaelite paintings were frequently regarded as assaults on the eye, objectionable in their realism, and morally shocking.

Tate Britain: Ophelia by Sir John Everett Millais 1851 – 52. Photo Credit: © Ingrid Wallenborg.

Tate Britain: Ophelia by Sir John Everett Millais 1851 – 52. Photo Credit: © Ingrid Wallenborg.

A BRITISH TRAILBLAZER – Norham Castle, Sunrise by JMW Turner

The Clore Gallery at Tate Britain is home to the world’s largest collection of works by Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851). A master and innovator, he challenged the style of the old masters, revolutionising technique and subject matter. Described as the ‘father of modern art’ by John Ruskin, Turner often shocked viewers with his loose brushwork and vibrant colours while portraying the development of the modern world like no one before him. This is one of his late pictures, initially considered to be ‘unfinished’ by bewildered contemporaries. Indeed, you have the impression that he has painted not so much the objects he saw as the light and atmosphere surrounding them. However, throughout the twentieth-century appreciation of these pictures grew, especially in the case of Norham Castle, which has gradually become the embodiment of many ideas about Turner’s later style; reducing content while emphasising the play of light and colour.

Tate Britain: Norham Castle, Sunrise by JMW Turner c. 1845. Photo Credit: © Ingrid Wallenborg.

Tate Britain: Norham Castle, Sunrise by JMW Turner c. 1845. Photo Credit: © Ingrid Wallenborg.

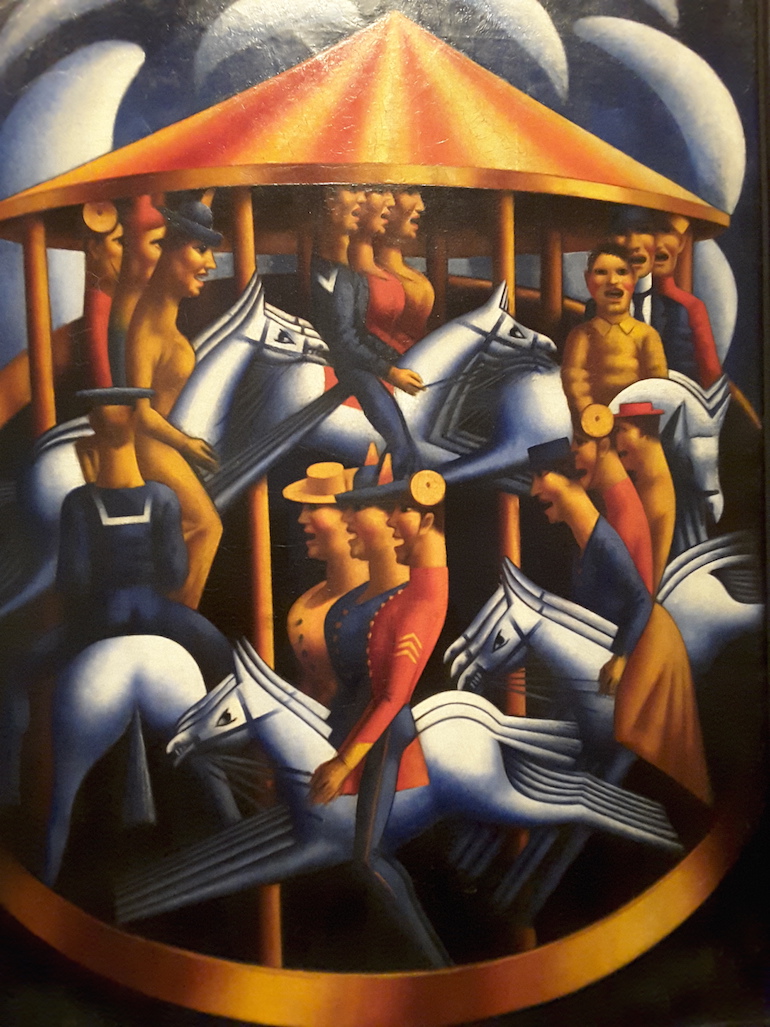

REPRESENTING ‘MODERNITY’ – Merry-Go-Round by Mark Gertler

The early 20th century was a period of extraordinary change; there was a great sense of energy and artistic dynamism as Britain was becoming a modern nation at the centre of an empire. Mark Gertler, a British Jew, was a ‘passivist’ and opposed to the war’s “wretched sordid Butchery.” His powerful image of uniformed men and stereotyped women revolving on a carousel, mouths open in an apparently endless scream, was seen by DH Lawrence in 1917, and he wrote to the artist: “I have just seen your terrible and dreadful picture Merry-go-round. This is the first picture you have painted: it is the best modern picture I have seen: I think it is great and true. But it is horrible and terrifying”. These stiff, simplified figures appear to be stuck inside a mechanical nightmare of machine-age militarism, meaninglessly spinning round and round. Strangely, when the painting was first exhibited, critics did not connect it to war and militarism. But they saw something so new and shocking it didn’t make sense.

Tate Britain: Merry-Go-Round by Mark Gertler 1916. Photo Credit: © Ingrid Wallenborg.

Tate Britain: Merry-Go-Round by Mark Gertler 1916. Photo Credit: © Ingrid Wallenborg.

‘THE DIVINE EXCENTRIC’ – The Resurrection, Cookham by Sir Stanley Spencer

Once called ‘the divine fool of British art,’ Stanley Spencer received mixed reviews during his lifetime. Residents of his beloved village of Cookham remember him pushing a pram full of paints around the local cemetery and wearing his pajamas under his clothes when the weather was cold. The way he combined biblical themes with contemporary situations shocked many, who failed to share his view of Cookham as the New Jerusalem. His paintings were the result of extremely powerful draughtsmanship informed by a mystical, magical inner vision. Spencer developed a highly individual style to express this vision. According to one writer, it was as if ‘a Pre-Raphaelite had shaken hands with a Cubist’. ‘The Resurrection’ was painted between 1924 and 1926 in a studio in Hampstead. When shown for the first time, one critic described it as “the most important picture painted by any English artist in the present century.”

Tate Britain: The Resurrection, Cookham by Sir Stanley Spencer 1924 – 27. Photo Credit: © Ingrid Wallenborg.

Tate Britain: The Resurrection, Cookham by Sir Stanley Spencer 1924 – 27. Photo Credit: © Ingrid Wallenborg.

A MODERN MASTER SCULPTOR – Recumbent Figure by Sir Henry Moore

This is the first of Moore’s artworks to enter Tate’s collection in 1939. He emerged in the 1920s as a leading avant-garde figure. Inspired on the one hand by African and Oceanic art seen in the British Museum, the forms seen in his sculptures often derive their shapes from natural objects such as stones, bones, and sticks that he found in the countryside. ‘Recumbent Figure’ shows the female figure undulating like the landscape. Commissioned by the architect Serge Chermayeff to be situated on the terrace of his home in Sussex, it was carved from a block of English Green Hornton stone. The reclining figure is a subject with a long history in both Western and non-Western art, and Moore believed that because the subject was so well known, he did not have to represent his figures naturalistically; instead, he was able to experiment with ‘formal ideas.’ In this work, you can detect influences from ancient Toltec-Maya culture as well as from Pablo Picasso.

Tate Britain: Recumbent Figure by Henry Moore OM 1938. Photo Credit: © Ingrid Wallenborg.

Tate Britain: Recumbent Figure by Henry Moore OM 1938. Photo Credit: © Ingrid Wallenborg.

POST-WAR REACTION – Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion by Francis Bacon

First shown in London in April 1945, this work provoked immediate consternation. One writer went as far as to claim that ‘there was painting in England before the Three Studies, and painting after them, and no one … can confuse the two’. The painting of three pale figures with distended necks, isolated against a hot orange background, is invested with a raw power that is both unsettling and remarkably repressive. Bacon later related these distorted creatures to The Eumenides, vengeful furies of Greek mythology. Of course, the title itself refers to the crucifixion, a horrendous form of execution that sits – not without contradiction – at the heart of the Christian faith. With deficient limbs, these bodies appear surreal, tortured by stress and pain, perhaps evoking the new pessimistic post-war world of Nazi concentration camps and nuclear weapons. In the words of Francis Bacon himself: “When I am told that my paintings are disturbing, poignant or shocking, I wonder if life isn’t even more disturbing, poignant or shocking.”

Tate Britain: Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion by Francis Bacon. Photo Credit: © Ingrid Wallenborg.

Tate Britain: Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion by Francis Bacon. Photo Credit: © Ingrid Wallenborg.

Note: Since its creation in 1984, Tate Britain is also home to the annual Turner Price, awarded under much media scrutiny to an outstanding British artist. Whoever wins the prize continues to provoke a healthy debate about all aspects of the visual arts. After a fact-filled and enlightening tour of Tate Britain led by a Blue Badge Tourist Guide, you will be even better armed to join this debate!

Leave a Reply