In 1799 Thomas Bruce, the Seventh Earl of Elgin, was appointed ambassador by the British government to the Ottoman Court of Turkey, which then ruled Greece. Within twenty years of his appointment, many of the carvings from the Parthenon, the Temple of the goddess Athena, were transported to London. These used to be referred to as the Elgin Marbles but are now normally called the Parthenon Marbles in honour of where they came from and not who was responsible for bringing them to London. The Parthenon Marbles can be seen in the Duveen Gallery of the British Museum, which has been open since 1962.

This is not the end of the story, however, because the Greeks – and many of their supporters around the world – want these carvings to be returned to Greece. There is a specially built museum at the Acropolis, the hill on which the temple still stands, and space there for the marbles to be put on display should they ever be returned to Athens.

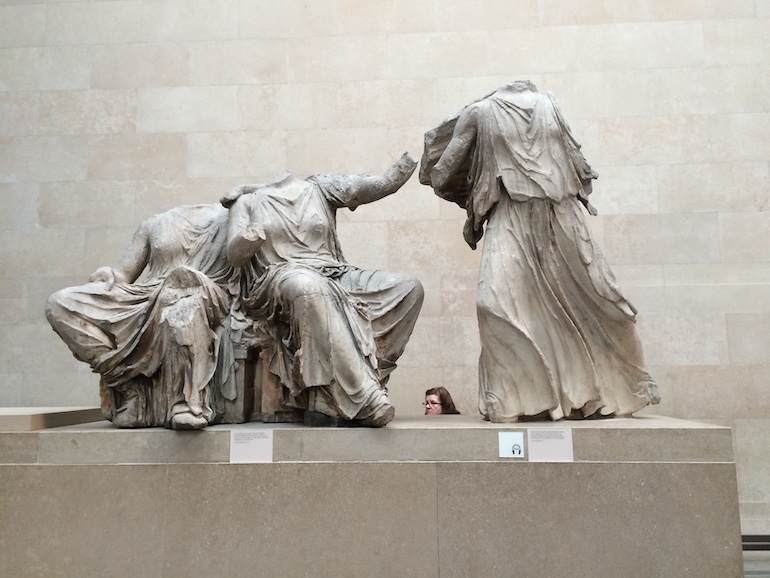

Four Gods, part of the Parthenon Marbles in the British Museum. Photo Credit: © Edwin Lerner.

Four Gods, part of the Parthenon Marbles in the British Museum. Photo Credit: © Edwin Lerner.

Campaign to return the Parthenon Marbles to Greece

The British Museum argues that the Parthenon Marbles were legally acquired by Lord Elgin and are their rightful property. If they were to return the Parthenon Marbles, then every country that had lost its treasures in the past to acquisitive and/or well-meaning British collectors would want them back, and the museum would be effectively emptied of its contents.

The campaign to return the Parthenon Marbles to Greece began almost as soon as they came to London. The poet Lord Byron, who was a contemporary of Elgin, described their removal as ‘vandalism’ and ‘looting.’ Elgin, who had originally intended to decorate his own house with the marbles but was forced to sell them to the British government because of his financial problems, defended his actions in bringing them to London, but the campaign to return them is gathering steam, and has support from well-known actors George Clooney and Stephen Fry.

This campaign first attracted widespread media attention when another actor, Melina Mercouri, became Greek Minister for Culture and vigorously lobbied for their return. She can be seen on YouTube in the Duveen Gallery in a scene from the film Phaedra with a young Anthony Perkins, who plays her stepson. Mercouri came to London to see the Marbles and had a debate with the Director of the British Museum about their future, but he and the museum refuse to change their attitude, and Mercouri died in 1994 without achieving her aim of returning the marbles to Athens where they were first created.

Pediment horse, part of the Parthenon Marbles in the British Museum. Photo Credit: © Edwin Lerner.

Pediment horse, part of the Parthenon Marbles in the British Museum. Photo Credit: © Edwin Lerner.

History of the Parthenon Marbles

The Parthenon Marbles date from the fifth century BC when Athens was ruled by Pericles, who had won fame as a general fighting the Persians, the same people who were later to rule Greece as part of the Ottoman empire. He became the First Citizen of Athens and ruled from 461 BC to his death (probably from the plague) in 429 BC. The period when he was in power is often referred to as ‘the age of Pericles’ or as the ‘golden age of Athens.’

Greece was not a unified country during this period but consisted of a series of city-states, of which Athens was the most famous and most powerful, Sparta the most warlike and aggressive. It was in Athens that democracy was born, the freemen of the city (not the women or slaves) determining its future. According to legend, Athena had been adopted as the patron goddess of the city after a competition with Poseidon, the god of the sea. Athena offered the people of Athens an olive tree, while Poseidon offered them salt. Athena’s gift was considered more valuable, so she was adopted as patroness of the city.

Every year the citizens of Athens marched in a procession to honour Athena at the Parthenon on top of the Acropolis, and every fourth year, a special festival known as the Panathanaea was held in which the citizens gave her a new cloak, known as a peplos, which had been woven over the previous nine months by the maidens of Athens. It was this procession that is the subject of the frieze running around the inside of the Duveen Gallery in the museum.

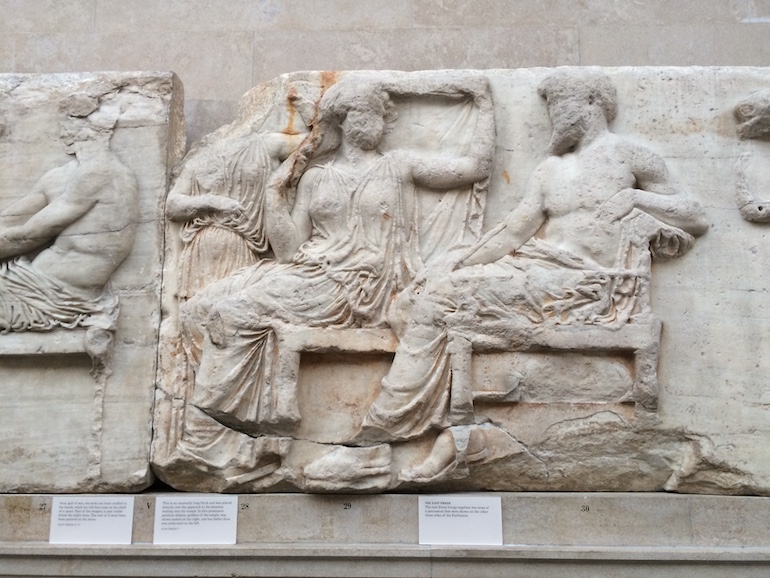

Two Gods, part of the Parthenon Marbles in the British Museum. Photo Credit: © Edwin Lerner.

Two Gods, part of the Parthenon Marbles in the British Museum. Photo Credit: © Edwin Lerner.

Apart from the procession of the people of Athens to the Acropolis, the Duveen Gallery also contains carvings in high relief from the metopes on the outside of the temple. These show a battle between the Lapiths and the half-man/half-horse Centaurs, who had been invited to a wedding but had drunk too much and tried to abduct the Lapith women – leading to a bloody battle. This was seen by the Greeks as a war between civilisation and barbarism.

Elgin also brought back from Athens some of the badly damaged carvings of the east and west pediments on the Parthenon, which show gods and goddesses present at the birth of Athena when her brother Hephaestos struck her father Zeus on the head to release her. She had been growing inside him, causing Zeus terrible headaches after he had swallowed her mother Metis, having heard a prophesy that she would bear a child who would eclipse him.

The gods and goddesses of the ancient Greeks were also portrayed on the frieze that runs around the inside of the Duveen Gallery. They can be seen opposite the entrance to the gallery sitting down so as to accommodate their greater height inside the restrictions of a one-metre frieze. Here we see the messenger god Hermes wearing his winged sandals, the crippled Hephaestos holding a crutch, Hera, the wife (and sister) to Zeus as well as Ares, the god of war, holding his knee impatiently as if ready for action, while the god of wine Bacchus raises a now missing glass as if in the act of toasting someone. These figures would all have been familiar to ordinary Athenians joining the procession to their patron goddess Athena.

Pediment Hebe, part of the Parthenon Marbles in the British Museum. Photo Credit: © Edwin Lerner.

Pediment Hebe, part of the Parthenon Marbles in the British Museum. Photo Credit: © Edwin Lerner.

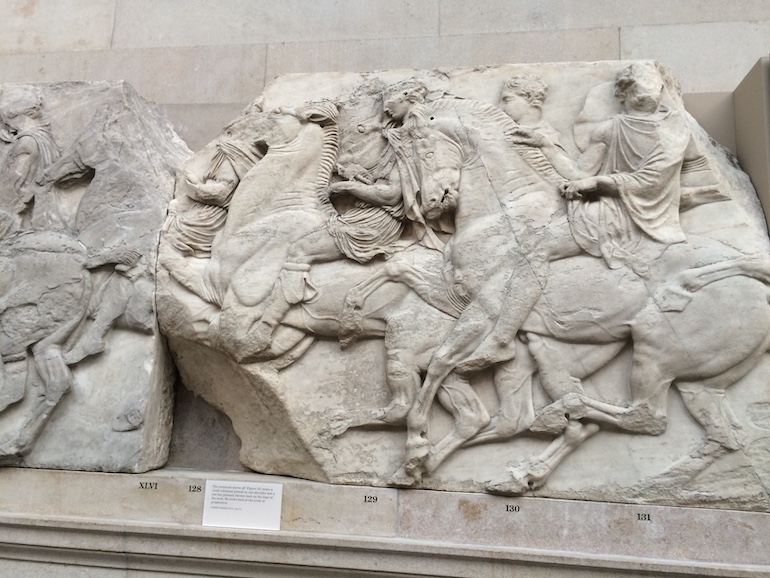

The procession was a secular subject, unusual in Greek temples, but here was a chance to showcase the talents of the sculptors of Athens led by the great Phiddias. Look at the lines of horsemen, sometimes impatiently restraining their steeds, at other times galloping ahead when they have space and time. The carvings were only six centimetres deep, but such was the skill of the sculptors they could show several horses in a line. You can also see holes where leather (long since perished) would be attached to show the reins of the horses. The carvings were brightly painted but are now white, the colour having been removed through the effects of weathering and over-enthusiastic cleaning by the workmen of the gallery’s donor Lord Duveen.

The chief sculptor Phidias, who was a friend of Pericles, also created a twelve-metre high statue of the Athena inside the Parthenon. This has since been lost as the temple was badly damaged in a war between the Turks and the Venetians in 1687 when it was used as a gunpowder store and was hit by a cannonball, the resulting explosion killing 300 people.

The Parthenon was in a state of ruin when Elgin arrived as ambassador to view it, and he was concerned about the future of the sculptures it contained. At first, he wanted just to take drawings of these sculptures but eventually decided that they needed to be saved by being brought to London. He received authorisation in the form of a permit, or ‘firman’, issued by the Turks (not the Greeks) to take them away, The process of removing and bringing the marbles to London cost Elgin £75,000 and the British government only paid him £35,000 for them so he made a considerable loss on the transaction.

Three Gods, part of the Parthenon Marbles in the British Museum. Photo Credit: © Edwin Lerner.

Three Gods, part of the Parthenon Marbles in the British Museum. Photo Credit: © Edwin Lerner.

Some people see Elgin as the hero of the story – others as the villain. It is probable – but not definite – that the marbles would have decayed further if they had been left in place. Their removal to London can be seen as a rescue operation by some, as an act of little more than theft by others, an arrogant Briton treating the feelings of the locals with disdain – or ignoring them completely – as he helped himself to the treasures of the ancient world.

The British Museum is full of objects which have been removed from their places of origin. It may, in fact, be the worst named museum in the world as around ninety per cent of its exhibits come from outside Britain. Many of the countries that were obliged to give up their treasures now want them back. These include a moai or statue from Easter Island in the Pacific, which is now part of Chile. The very name of this island is Eurocentric, as it was first alighted on by a Dutch ship on Easter Sunday 1722, and it is often now referred to by the indigenous name of Rapa Nui. Other famous objects a long way from their original homes are the Rosetta Stone, which first unlocked the language of hieroglyphs, and the Benin Bronzes from Nigeria, all of which were removed without the permission of local people.

As a Blue Badge Tourist Guide who sometimes takes people and groups to the British Museum, I often hear the arguments for and against the Parthenon Marbles and other high-profile cultural artefacts returning to their country of origin. One positive of having them at the British Museum is that millions of people have been able to see them free of charge each year. One of London’s most popular tourist attractions, entrance to the British Museum is free and includes access to its permanent galleries. The only exception is for special exhibitions, which usually require a fee.

Horses, part of the Parthenon Marbles in the British Museum. Photo Credit: © Edwin Lerner.

Horses, part of the Parthenon Marbles in the British Museum. Photo Credit: © Edwin Lerner.

Leave a Reply