In May 2021, Queer Britain, the UK’s first museum dedicated to LGBTQ+ (lesbian, gay, bi, trans, queer) history and culture, opened in the King’s Cross area of London. Located at 2 Granary Square, it joins destinations including Berlin, San Francisco, and Fort Lauderdale in having a permanent queer museum space.

And it’s not before time: same-sex marriages were celebrated here from 2014, gay computer scientist Alan Turing features on our £50 note, and many museums and attractions in London have LGBTQ+ themed events, trails, and exhibits. Indeed, research shows that London is the leading city in Europe for LGBTQ+ tourism, while the census of 2021 showed that some boroughs of the city (Lambeth, Southwark, City) have an LGB+ residential population higher than 8%, compared to an average of 3% across England and Wales.

NOTE: The word ‘queer,’ once a homophobic term, has a rich recent history of being used positively, particularly for younger generations, as an umbrella term to refer to non-straight and non-gender-conforming identities.

Entrance to the Queer Britain museum in London. Photo Credit: © Ric Morris.

Entrance to the Queer Britain museum in London. Photo Credit: © Ric Morris.

Exhibition: We Are Queer Britain

Located in a renovated Victorian industrial building, the King’s Cross space is dedicated to temporary exhibitions on LGBTQ+ themes. I visited during the inaugural exhibition We Are Queer Britain (until April 2023), marking the 50th anniversary of London’s first Pride march, which reflects on a century of activism, art, culture, and social history.

Sexual relations between men were illegal in England and Wales until 1967 (until 2000 in the armed forces), and probably the most famous person to be imprisoned for their sexuality was Oscar Wilde, author of The Picture of Dorian Gray and The Importance of Being Earnest. His cell door from Reading Gaol is on display here alongside a copy of his heartfelt testimony, which he wrote behind that door, De Profundis.

Exhibition room in Queer Britain museum in London. Photo Credit: © Ric Morris.

Exhibition room in Queer Britain museum in London. Photo Credit: © Ric Morris.

While lesbian relationships have never been illegal in this country, they have often been ignored or forgotten, and this is why queer history is so important – it reclaims stories previously left out. Often we get a glimpse into people’s lives through their diaries, such as the writer Virginia Woolf, whose bust is on display here, and 19th century Yorkshire landowner Anne Lister, whose coded diary has been called ‘the Rosetta Stone of lesbian history.’

An exciting discovery of recent years is the diary of Mr. Lucas (1926-2014) – civil servant by day and chronicler of London’s gay underworld by night. You can see a page from his diary here, and we eagerly await their full publication. Another moving document is from Switchboard, an LGBTQ+ telephone helpline founded in London in 1974 – a vital lifeline when information and support was hard to come by – and each phone call was documented in their log books, which today provide a rich insight into the issues faced by queer people from the 1970s to the 1990s, and subject of an award-winning podcast The Log Books.

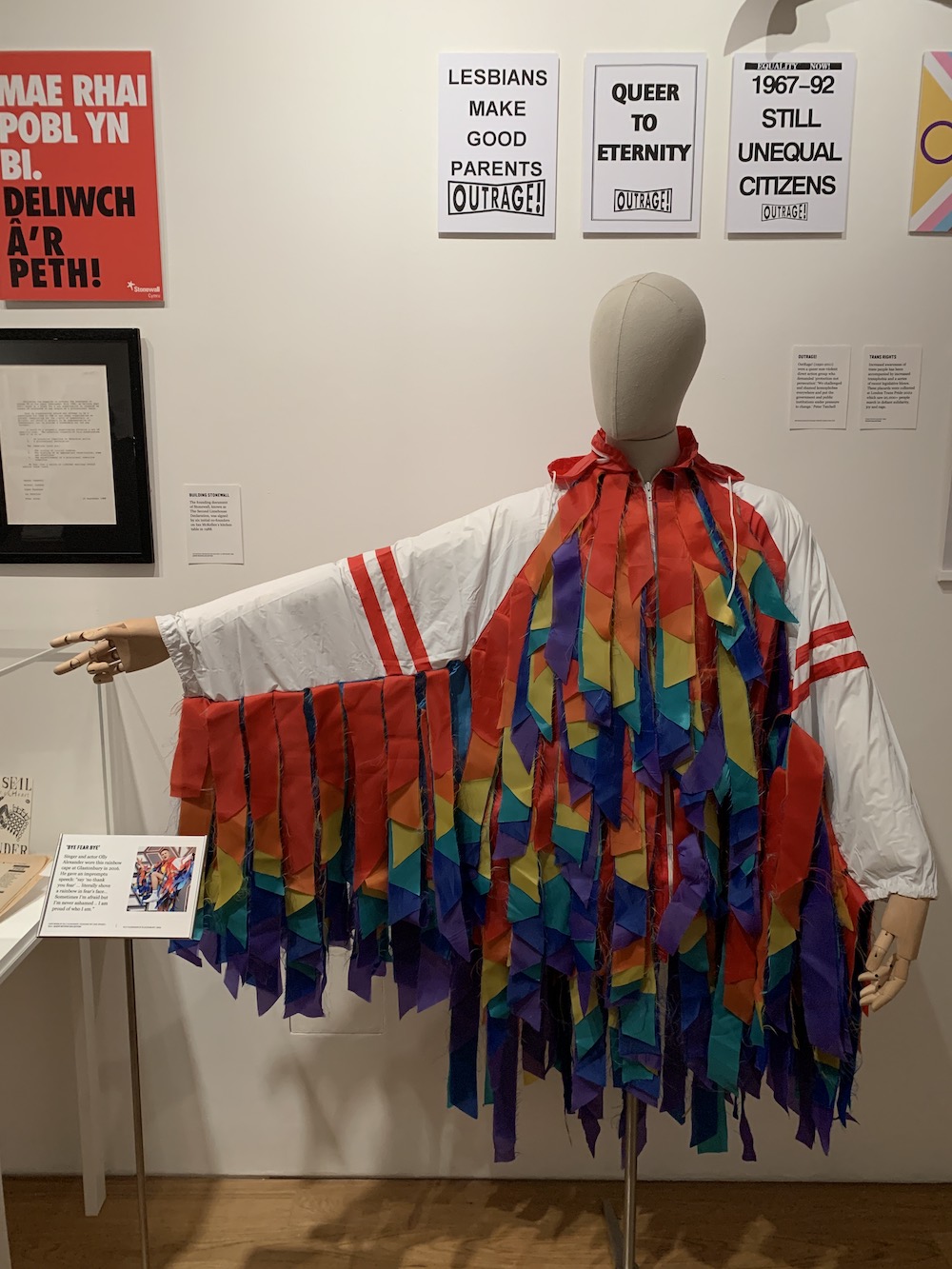

Rainbow cape worn by singer Olly Alexander. Photo Credit: © Ric Morris.

Rainbow cape worn by singer Olly Alexander. Photo Credit: © Ric Morris.

Also on display is a cabinet from the Museum of Transology, the UK’s most significant collection of objects representing trans, non-binary and intersex people’s lives, who have often been sidelined even within queer history. There are fashion items too – Pride outfits worn by members of LGBTQ+ Muslim organisation Imaan, a dress worn by the ‘Godzilla of drag queens’ Divine during their UK tour, and the rainbow cape worn by singer Olly Alexander for his Glastonbury Festival set.

As the exhibition marks the 50th anniversary of London’s first Gay Pride march (as it was called then) in 1972, there are photos and memories of early prides. For many people attending, their first pride was the first time they were ‘out’ in public and their first encounter of the size and strength of the community. The first pride commemorated the 1969 riots outside the Stonewall Inn in New York when LGBTQ+ people resisted a police raid. For this reason, the name Stonewall was chosen for the UK’s most influential LGBTQ+ charity, formed in 1989 by leading activists, including actor Ian McKellen (Gandalf in Lord of the Rings). Stonewall successfully campaigned to remove anti-LGBTQ+ laws, equalise the age of consent and introduce legal same-sex partnerships. On display is the founding document of Stonewall, signed in Ian McKellen’s kitchen.

Queer Britain packs a lot into a compact space. You can read books in the small library, curated by Gay’s The Word, Britain’s oldest LGBTQ+ bookshop based in nearby Bloomsbury. You can buy many of these books in the museum shop, along with greeting cards, mugs, and items created by selected community artists. And if you can’t make it to the museum, they have the beginnings of a digital archive on their website – you can rotate and zoom a 3-D scan of Oscar Wilde’s prison cell door.

The shop at Queer Britain museum in London. Photo Credit: © Ric Morris.

The shop at Queer Britain museum in London. Photo Credit: © Ric Morris.

Filling in the gaps

So, why do we need a queer museum? Quite simply, it fills in the gaps. In the past (and in much of the world, in the present), people whose sexuality or gender identity differed from the norm were ignored, misunderstood, or punished. Many people protected themselves by keeping themselves off the record. On top of that, archivists and historians have overlooked, explained away (‘they were… friends’), and destroyed evidence of non-conforming lives. For instance, when bisexual poet Lord Byron died, his friends immediately rushed to his publishers in Mayfair and burned his memoirs. Who knows how many queer memories went the same way?

But far more than enriching the historical record, a queer museum helps people today understand and explore their place in the world. Many LGBTQ+ people remember a time when they were not represented in ‘respectable’ culture when there were no positive models of who they could be, when they had to figure out life on their own. Sue Sanders, the founder of LGBT+ History Month, says, ‘the difference it would have made to me as young person to know that Virginia Woolf was bisexual, to know about Oscar Wilde, would have made a phenomenal difference to my life.’ The role of community museums, we are reminded, is more than to archive dusty old relics: they have the power to crystallise shared human experiences.

People relaxing next to the Regent’s Canal, outside Queer Britain. Photo Credit: © Ric Morris.

People relaxing next to the Regent’s Canal, outside Queer Britain. Photo Credit: © Ric Morris.

King’s Cross: London’s new public space

Another reason to visit Queer Britain is to explore the recently-redeveloped King’s Cross area – a five-minute walk north of the famous station (and its neighbour St Pancras International). In the 19th century, this was a railway, canal, and road interchange where goods from northern England were unloaded to power and feed the capital. In the 21st century, these once-derelict railway lands have been repurposed to create a vibrant area for shopping, eating, drinking, studying, and working. Queer Britain neighbours include the world-famous art college Central St Martins and the landmark new Google building (with a 300 metre-long roof garden) designed by Thomas Heatherwick, the multi-talented creator of the 2012 Olympic cauldron and the latest model of the red London bus.

IFO (Identified Flying Object) by Jaques Rival at King’s Cross Station in London. Photo Credit: © Ursula Petula Barzey.

IFO (Identified Flying Object) by Jaques Rival at King’s Cross Station in London. Photo Credit: © Ursula Petula Barzey.

Explore further

If you want to find out more about the heritage and regeneration of the King’s Cross area around the Queer Britain museum, you can go on a London Architecture Tour – Modern and Contemporary.

If you want to explore London’s rich and varied LGBTQ+ life, the first stop would be Soho, with its bars, restaurants, and heaps of cultural heritage. For history, the nearby district of Bloomsbury was the home of many leading writers and intellectuals who we would now call LGBTQ+. Why not get the most out of your visit with an expert Blue Badge Tourist Guide?

I’ll finish with a quote from London’s first openly-gay celebrity, Quentin Crisp:

‘Time is on the side of the outcast. Those who once inhabited the suburbs of human contempt find that without changing their address they eventually live in the metropolis.’

Leave a Reply