The Tate Modern in Southwark has become one of the most popular museums in the world since it was converted from its former use as a power station and opened by the Queen in 2000. It is one of four galleries in Britain created from the legacy of the sugar entrepreneur Henry Tate. These are the original Tate Gallery (now Tate Britain), Tate St Ives and Tate Liverpool.

Much of the free collection at Tate Modern was changed during the pandemic. Artworks were replaced, removed, re-positioned. Visitors now circumambulate the galleries in one direction only. This is what I offer as a tour of the highlights.

We begin on the second floor in The Artist’s Studio with Pierre Bonnard’s Le bol de lait (1919). The artist was one of the nabis (prophets) who said ‘before it is a horse or nude, a picture is a flat surface with colours in a certain order’. The sunlight and the window frame present geometric shapes. The brain interprets three dimensions. Modern art undid the trick and returned to two. On the right is Duncan Grant’s Interior at Gordon Square (1917) in which the rectangles have fully taken over. Grant was in the Bloomsbury Group of arty intellectuals who met at that address to discuss art, science, politics and sex.

Pierre Bonnard Le Bol de Lait (1919). Photo Credit: © Richard Jones.

Pierre Bonnard Le Bol de Lait (1919). Photo Credit: © Richard Jones.

In the first decade of the twentieth century the fauves (wild beasts) led by Henri Matisse, reacted against impressionism in vibrant colour and violent forms. Matisse’s Le Dos (1909-1930) – four sculptures of a woman’s back – is across the room. They progress from hard-etched surfaces to stark simplicity. Matisse was still bewildering viewers through colour late in life and in L’Escargot (the snail 1953) he deliberately juxtaposes primary and secondary hues for the jarring effect – red against green, blue versus orange, yellow meeting pink. Unable to wield a brush in his dotage, he turned to collage and called it ‘painting with scissors’!

Henri Matisse L’Escargot (1953). Photo Credit: © Rick Jones.

Henri Matisse L’Escargot (1953). Photo Credit: © Rick Jones.

The fauves were a sensation but, by the second decade of the century, the fickle Parisian public had discovered Pablo Picasso, who found a new direction in Cubism. In the centre of the room, his Head of a Woman (1909) is a sculpture modelled by his volatile lover Fernande Olivier. The fragmented facets become multiple simultaneous viewpoints, matched in two dimensions by the work of fellow-Cubist Georges Braque on the wall nearby. La Mandore (1909) depicts a lute-like instrument whose vibrating strings seem to pixelate the image.

Pablo Picasso Tete de Femme (1909). Photo Credit: © Richard Jones.

Pablo Picasso Tete de Femme (1909). Photo Credit: © Richard Jones.

We enter the Surrealists’ gallery of paintings in the aftermath of the First World War. Straight ahead is Picasso’s Les Trois Danseuses (1925), which was an inspiration through its nightmare anguished faces and contorted bodies. Picasso designed for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes so the dancers are professionals in the savage choreography perhaps of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. Picasso married dancer Olga Khokhlova in 1919. Adjacent is the comical dream image of Joan Miro’s Head of a Catalan Peasant (1925) with a sense of the absurd in the straggly beard, wide eyes and rustic hat. In the same corner is one of the most beautiful forms in Tate Modern, Henry Moore’s Composition (1932), a voluptuous head and shoulders welling up from the sculptor’s vivid subconscious.

Opposite is Salvador Dali’s Autumnal Cannibalism (1936) in which two faceless figures eat each other in a landscape recognisably the artist’s home. The Spanish Civil War began that year. Near it hangs L’homme au journal (1928) by Belgian Surrealist Rene Magritte, pervaded by a dreamlike silence, stillness and absence. The sense of loss in 1920s Europe was an incurable ache.

Abstract art attained ideal form in Dutch painter Piet Mondrian whose Composition C (1935), rectangles with heavy outlines and primary colours, has become a fashion icon. Dutch art makes a triumvirate of Rembrandt, Van Gogh and Mondrian.

The thrill of the twentieth century was felt by the Futurists, an Italian movement whose members would-be devotees of Mussolini. Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913) by Umberto Boccioni delights in the sensation of speed and mechanisation. Boccioni wrote in the Futurist Manifesto in 1912 of ‘a new beauty, a roaring car running like a machine gun.’

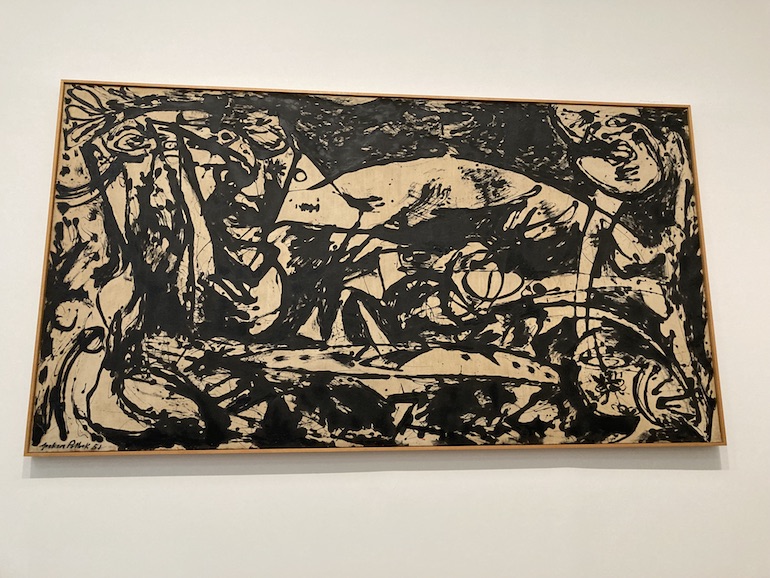

The reaction to the Second World War – Art after Catastrophe – is focused on Jackson Pollock’s Number 14 (1951). His work ‘has fire, is unpredictable, undisciplined, spills out of itself in mineral prodigality not yet crystallised’ said one critic. He rolled naked and drunk in the spilled, wet paint and wielded brushes tied to long poles. It was ‘action art’ or ‘all over painting’ and he died in a car crash with no one else involved in 1956.

Jackson Pollock Number 14 (1951). Photo Credit: © Richard Jones.

Jackson Pollock Number 14 (1951). Photo Credit: © Richard Jones.

Artists confused that their traditions had led only to the destruction of war, turned to chance as an element in painting. Cage I-VI (2006), by German painter Gerhard Richter was created with a canvas and a squeegee mop. No delicate brushstrokes here! The works are named after composer John Cage who wrote random music and one-piece (4’33”) of complete silence except for the accidental sounds in the concert hall. Richter, an East German who fled to the west weeks before partition in 1961, is one of the richest people in Germany through his art.

Can you invent a colour? the caption next to Yves Klein Blue asks. The artist Yves Klein did so here. Paints are chemicals and chemical companies define their hues in scientific coordinates and names – avocado green, burnt umber, raw sienna, magnolia. Opposite is a series of square canvases called The History of Painting by the British artist Maria Lalic. Each represents an era and is painted in a mixture of the pigments then available. Cave Yellow comprises the charcoal, earth and chalk at cave dwellers’ disposal.

Monochrome and colour are adjacent in Andy Warhol’s Marilyn Monroe’s Lips (1962). The lips are taken from a still for the film ‘Niagara’ (1953) in which the unknown Monroe was given top-billing and began her stratospheric rise. The lips are replicated a hundred times on each canvas. In colour, they are silk-screened in lipstick-red while a background of pink is superimposed in rough painting round them, the obvious human touch contrasting with the mechanistic repetitions.

Andy Warhol Marilyn Monroe’s Lips (1962). Photo Credit: © Richard Jones.

Andy Warhol Marilyn Monroe’s Lips (1962). Photo Credit: © Richard Jones.

The British Library (2014) by the Nigerian Yinka Shonibare CBE comprises 6,000 shelved books with the names of British immigrants in gold lettering on the spine – Didier Drogba, TS Eliot, Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, etc. The books are covered in the coloured fabrics of Africa though their history is Indonesian. Dutch colonists mechanised the weaving process and flooded the African continent with them and so we come to a sequence of galleries in which art and politics intertwine.

British artist Richard Hamilton painted The Citizen in 1983 inspired by the IRA ‘dirty protest’ in Ulster’s Maze Prison. The British government refused terrorists the status of political prisoners so they wore blankets and daubed their cells with excrement. Though apolitical, Hamilton was struck by their Christlike appearance and the similarity of the walls to cave paintings.

Hamilton appears in the next room in the video Information Action, a six-hour artistic question-and-answer session led by Joseph Beuys at London’s Tate Gallery in 1972. Hamilton presses Beuys about a previous Action explaining art to a dead hare. The excerpt lasts half an hour. It is followed by Beuys’ monumental sculpture Lightning with Stag in its Glare (1985) which makes a statement about the primal energy of the earth.

Duncan Grant Interior at Gordon Square (1915). Photo Credit: © Richard Jones.

Duncan Grant Interior at Gordon Square (1915). Photo Credit: © Richard Jones.

‘Actions’ to Beuys included teaching and the blackboards he filled became artworks exhibited here. In the video, fellow artist Gustav Metzger, a kindertransport immigrant to Britain in 1939, challenges Beuys on his failure to grasp alternative technologies. A room devoted to Metzger’s auto-destructive art follows. In the preparatory models for Stockholm June (1972), toy cars are displayed first in car-park order and second in a destructive tumble as a result of the corrosive power of exhaust fumes. A pupil of Metzger was Pete Townshend who destroyed guitars on stage as a member of the rock group The Who.

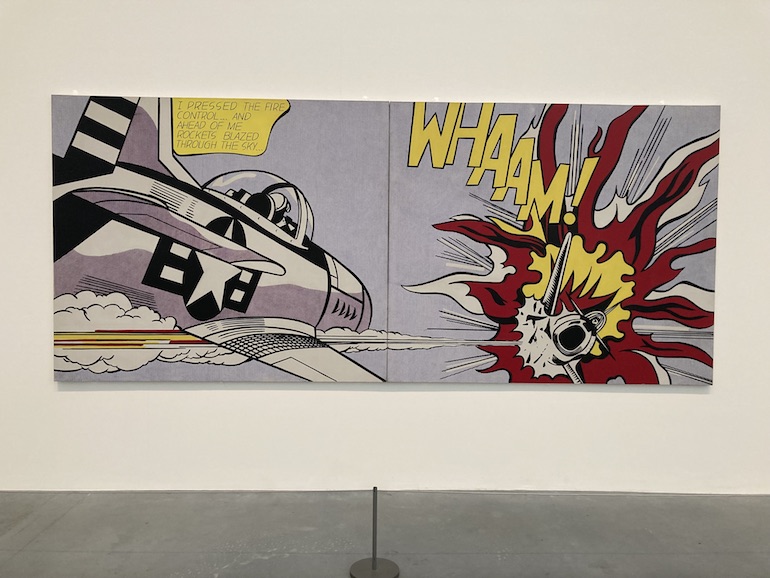

Pop Art was a product of the 1950s in Britain and the USA inspired by consumer artefacts, photos, adverts and cartoons often blown up to enormous size and painted garish colours. Roy Lichtenstein’s Whaam! announces itself with a burst of warplane gunfire in a giant painted image from the 1962 comic All American Men of War. This is no enlarged photo-image but an oil-on-canvas artwork.

Roy Lichtenstein Whaam! (1963). Photo Credit: © Richard Jones.

Roy Lichtenstein Whaam! (1963). Photo Credit: © Richard Jones.

Next to him is the British Pop Artist Eduardo Paolozzi who was obsessed with man’s relationship with machines and designed fantasy machines in art like his aluminium Mechaniks Bench (1963). He aimed to eliminate arty qualities. ‘The battle is to try to restore these anonymous materials into a poetic idea.’ He lived and worked in Edinburgh except for three years in Paris after the war when he met Paul Klee and Alberto Giacometti.

Finally, we return to the start of the twentieth century with Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain(1917), a porcelain urinal which the artist entered for an exhibition. It was the first so-called ‘ready-made’ or ‘found object’ and kick-started the debate about what exactly art is which has continued unresolved throughout the modern era. With this last statement, Tate Modern puts all the arguments into context.

Leave a Reply