A blockbuster exhibition at the National Gallery traces the travels of Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), the ‘Apelles of the black line’ as Erasmus called him. These journeys were principally to cities along the Rhine (1490-4), twice to Venice (1505-7), and the Netherlands (1520-21). No other artist has produced a comparable body of work from the experience of travel. Like the landmark self-portrait of 1500, which evokes Christ, Durer’s art signals a self-awareness that crosses frontiers. Not only is he the premier artist of the Northern Renaissance, but he is also a bearer of the German soul. Popular works such as The Hare (1502) and The Turf of Grass (1503) with their mastery of minutiae are national icons. The statue in his native city of Nuremberg is the oldest in Europe to honour an artist.

The National Gallery has pulled out all the stops for the Albrecht Dürer exhibition with 134 gallery loans of which 36 are paintings and 70 drawings (many double-sided) together with correspondence and colourful journal entries, at times sparklingly witty. The quality is stratospheric: we are treated to: Melancolia 1 (1515) the most interpreted print in Western art, the magical Christ Among the Doctors (1506) with its superlative characterisations, the learned all’antica symmetry of Adam and Eve (1504) as well as the double-sided Washington Haller Madonna and Child (1499) with its enticing assimilation of Netherlandish traditions.

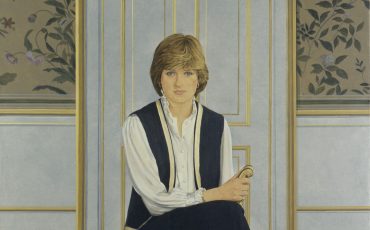

Madonna and Child oil on panel by Albrecht Dürer about 1496–9. Photo Credit: © Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC via National Gallery in London.

Madonna and Child oil on panel by Albrecht Dürer about 1496–9. Photo Credit: © Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC via National Gallery in London.

Who was Albrecht Dürer?

Albrecht Dürer hailed from the southern German city of Nuremberg. Nestling alongside the river Pegnitz with a population of 40, 000, it was the de facto capital for the Holy Roman Empire, the loose conglomeration of cities in western and central Europe. Nuremberg was where the Imperial Diets, or Parliaments, convened and where Imperial relics were kept. Scholars flocked to Nuremberg – twenty-seven trade routes ran through the town – and the city became a hotbed of learning in the arts, sciences, and mathematics. Albrecht Dürer, as the exhibition reveals in a series of pen and brown ink drawings, becomes increasingly preoccupied with mathematics, especially how it relates to the human figure. He also forges a life-long friendship with the foremost Nuremberg Humanist Willibald Pirckheimer, a graduate of law in Padua. Dürer wrote ten letters to Pirckheimer from Venice alone.

Nuremberg was also a manufacturing hub. Copper and silver mined in nearby Bohemia and Saxony were reworked metalworkers. Prosperity and patronage went hand in hand and the bourgeoisie filled their local churches with embellishments. Dürer’s father and grandfather were goldsmiths and it was a natural step for him to go into this lucrative profession. At fifteen he entered the workshop of Michael Wolgemut, a stained-glass specialist and Nuremberg’s top practitioner. Dürer recalled this formative period with affection and in the exhibition contains one of his prized possessions, an engraving of Christ by Wolgemut.

Wolgemut’s achievements were dwarfed by his pupil but he is important. He injects life into the archaic medieval woodcut and contributed illustrated woodcuts to The Nuremberg Chronicle, the world’s history from creation until 1493, and the first great illustrated book. Its charming recreations of cityscapes were to make an impression, an idea that the apprentice later carries with him on his travels. In 1490 Dürer heads to cities up and down the Rhine during his four-year ‘Wanderjahre’ (a ‘gap’ study) seeking a wider artistic outlook.

Albrecht Durer self portrait at 28 (1500). Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Albrecht Durer self portrait at 28 (1500). Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

He targets Colmar as it is where the master engraver Martin Schongauer lives but, frustratingly, arrives to find his idol has passed away only months earlier. Undeterred, Dürer resides with the engraver’s brother Georg who gives the impressionable artist access to the secrets of engraving. The National Gallery exhibition displays Schongauer’s The Road to Calvary (1485) which showcases the Netherlandish fashion for detail and sophistication, innovations in which Dürer excelled in his epoch-making Meisterstiche, particularly in copperplate. This technique, which combined woodcut printing and ornamental engraving on silver and gold was particularly suited to the artist with his training as a goldsmith.

The must-see Melancolia 1 exemplifies this. Italy beckons in 1495. Albrecht Dürer had only recently married, a wedlock of convenience, and the impetus to leave Nuremberg again may, apart from business interests have been due to the plague. Laden with travel-funding art and pocketing her dowry money (!), he sets off on an arduous trek to Venice without his new spouse Agnes. En route ensues wonderful vedute. Trintperg – Dosso di Trento of 1495 is typical and these works presage the future with their topographical accuracy and en plein air interest. The Nuremberg Chronicle prototype has been transfigured, and these sketches are the first of their kind in Western art.

Venice is alluringly exotic and he settles for more than a year. He paints a lobster and a sea crab is enthralled by the fashions of Venetian women as well as bypassing Ottoman Turks and traders. He gleans much from Venetian artists, not least in technique. Christ Among the Doctors (1506) is preceded by a thoroughness of study not found in his pre-Venice oeuvre. No less than twenty-two carta azzurra drawings result, a blue-dyed paper on which ink and white highlights are applied by brush – a Venetian conceit. We see a stunning Head of a Twelve Year Old, which is preparation for the figure of Christ. Poignantly, the National Gallery turns the tables by showing us how Bellini himself absorbs compositional devices from Durer’s engraving of The Prodigal Son (1496) in his The Assassination of St Peter Martyr (1507). The interchange between Durer and Venice, north and south, is fluid.

Christ among the Doctors oil on panel by Albrecht Dürer 1506. Photo Credit: © © Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid via National Gallery in London.

Christ among the Doctors oil on panel by Albrecht Dürer 1506. Photo Credit: © © Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid via National Gallery in London.

Albrecht Dürer’s final and most revelatory journey is to the Netherlands in 1520. As court painter to the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian (we see a sketch and portrait of him) he had received a healthy annuity of 100 florins (about £6,000 today) but in 1519 his protégé died. Dürer travels to petition the replacement incumbent Charles V in Aachen for a renewal. Departing this time with Agnes and a maid, he adopts a more diligent approach: a full diary is kept and this is often complemented by sophisticated silverpoint drawings – an art form that affords no ‘pentimenti’ or corrections. There are delicate views of churches in Aachen, the port of Antwerp as well as mimetically true depictions of zoo animals and a walrus. Sometimes disparate images coalesce on the same page as a superb mental collage. His curiosity leads him north to Zeeland to draw a beached whale, and we read of his disappointment on discovering that it had since perished.

Not to be missed as we unravel this story is a trust in the unconscious, which is rare at this time: Visions of a Cloudburst (1525) in watercolour and text is the first visual impression of a nightmare. We also survey a magnificent series of portraits of the rich and mighty. Each human likeness here is thoroughly Renaissance in its Humanistic promotion of individuality but Dürer makes physiognomic verisimilitude his own. It is perhaps no surprise to read in Albrecht Dürer’s journal that he was visited one day in his Venice studio by Giovanni Bellini. The gilded 80-year old patriarch passed by with the hope of discovering how the German artist achieved those almost unbelievable effects.

Note: The Credit Suisse Exhibition Dürer’s Journeys: Travels of a Renaissance Artist at the National Gallery in London is from 20 November 2021 – 27 February 2022. For more information including tickets, visit the National Gallery website.

Leave a Reply