Working as a Blue Badge Tourist Guide in I often show my guests – especially if they have young children – the bust of the William Buckland in the south aisle of Westminster Abbey. He may hardly be a household name but Buckland is memorialised for his appointment as Dean of the Abbey in 1845 and his work as an early palaeontologist and undergroundologist (geologist). He excelled at two of the new sciences that would enthral Britain in the nineteenth century.

Buckland’s career in the Church of England was helped by his scientific work, which led to him gaining a lucrative appointment as canon of Christ Church College, Oxford, a comfortable post which allowed him to lecture on geology and mineralogy and required only minor responsibilities. Notable figures who attended his lectures, which were held at Corpus Christi College, included the future cardinal John Newman of the Oxford Movement, Samuel Wilberforce, who would eventually butt heads with Darwin’s ‘bulldog’ T H Huxley in a memorable debate about evolution, and Charles Lyell, mentor to Darwin and author of The Principles of Geology, the publication that brought geology to the masses and popularised the idea that its processes are ongoing.

Buckland’s career in the Church of England was helped by his scientific work, which led to him gaining a lucrative appointment as canon of Christ Church College, Oxford, a comfortable post which allowed him to lecture on geology and mineralogy and required only minor responsibilities. Notable figures who attended his lectures, which were held at Corpus Christi College, included the future cardinal John Newman of the Oxford Movement, Samuel Wilberforce, who would eventually butt heads with Darwin’s ‘bulldog’ T H Huxley in a memorable debate about evolution, and Charles Lyell, mentor to Darwin and author of The Principles of Geology, the publication that brought geology to the masses and popularised the idea that its processes are ongoing.

Buckland’s work as a scientist had its roots in the growing interests of the gentry in emerging branches of natural philosophy, which included the disciplines of geology, mineralogy, palaeontology, anthropology, zoology and various other ologies. This was a generation that increasingly applied the scientific method to their enquiries (the term scientist was coined in 1834), relying on observation and experimentation to underpin their speculations. Palaeontology, the study of organisms that predate the Holocene (the last 11,700 years), was directly linked to geology as fossils of specific varieties are distributed within defined rock strata and sedimentary layers. Serious enquirers such as Buckland would not solely rely on the acquisition of specimens supplied by fossil hunters like Mary Anning but were increasingly taking to the field to study these finds on site, thus gaining a bigger picture in the understanding of their origin. Buckland’s enthusiasm and expertise were fed by his desire to unravel the secrets of the Lord’s Creation.

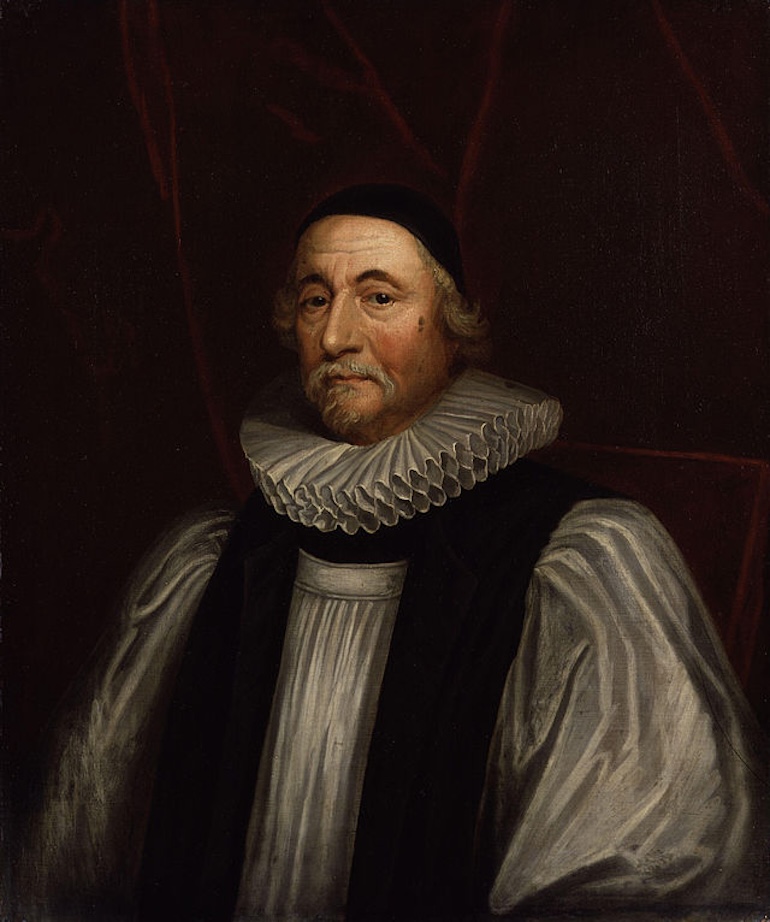

However, many of these new geological and paleontological discoveries and subsequent theories contradicted the traditional beliefs grounded in Biblical accounts of the creation of the world. Buckland, as a churchman, became one of the leaders of the Creationist camp in the ensuing intellectual battle that pitched them against those challenging the life work of Archbishop Ussher from the seventeenth century, which computed the date of Creation to 4006 BC, based on his analysis of the Old Testament. Ussher’s work earned him a state funeral, courtesy of Oliver Cromwell, and his grave is in Saint Paul’s Chapel in Westminster Abbey.

Archbishop James Ussher by Peter Lely. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Archbishop James Ussher by Peter Lely. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Buckland was President of the Geological Society on two occasions. This organisation gathered in the Freemason’s Tavern in Covent Garden and has been based in Burlington House since 1874. As a new branch of natural philosophy, geology owed a great debt to the Industrial Revolution, with many eighteenth-century engineers and entrepreneurs involved in canal building becoming increasingly aware and interested in the various layers found beneath ground level. Prominent names include William Smith, Josiah Wedgwood and James Watt.

Buckland’s first major discovery would start to undermine the timeline of the Great Flood, which was still a prominent feature in the explanation of geological processes such as finding shells at the top of mountains. Buckland’s thorough analysis of remains of hyenas (not native in the British Isles in modern times) found in the Kirkdale cave in Yorkshire led him to conclude they were not transported to the cave by the Great Flood but predated this cataclysm. For this work, he was awarded the Copley Medal by the Royal Society in 1822.

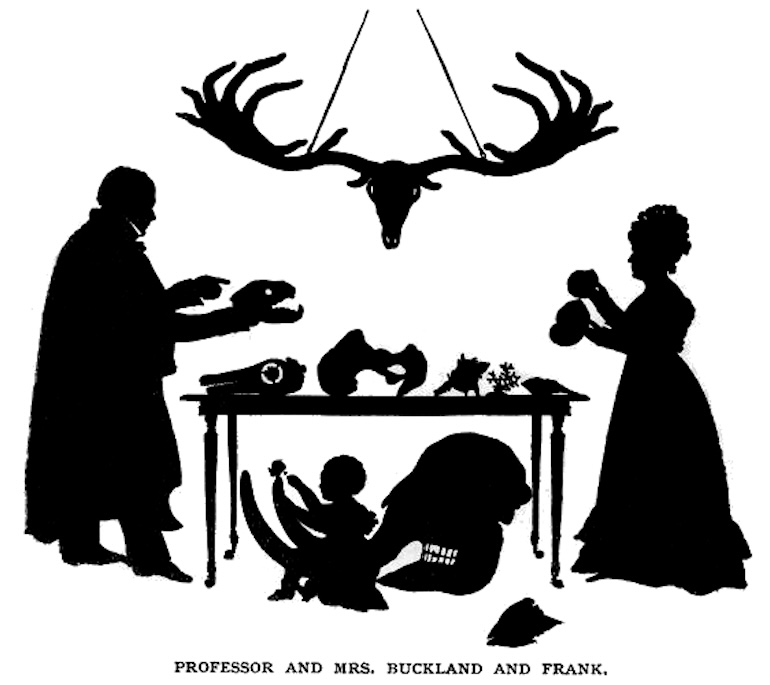

Six years later, William Buckland produced the first ever written account of a dinosaur, which he named Megalosaurus (Megalosaurus Bucklandii). This was based on a single 167 million-year-old fossilised jaw for which his wife, Mary Moreland, produced a detailed illustration. The term dinosaur would be coined twenty years later in 1841 by Richard Owen in reference to large, land-dwelling and extinct reptiles belonging to a separate branch of the order of lizards.

Buckland family silhouette. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Buckland family silhouette. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

In 1829, following observations by Mary Anning describing fossilised material in the stomach regions of ichthyosaurs (marine reptiles), Buckland concluded these to be faeces, naming them coprolites and establishing their importance in the understanding of species’ diet and behaviour.

Buckland was a popular figure in the early Victorian age, albeit a rather eccentric one. As a founding member of the Zoological Society in 1826, one of Buckland’s most perplexing projects was ‘eating his way through the animal kingdom’. This was a project he enthusiastically shared at home with family and guests who got to be treated to hedgehog, crocodile, mole and other peculiar dishes. Reminiscing about his undergraduate days, John Ruskin would fondly remember eating mice on toast at the Buckland’s table, surrounded by piles of rocks, minerals, fossils and the reverend’s exotic menagerie of animals, which included a bear named after the Assyrian emperor Tiglath Pileser.

The strangest meal Buckland attended took place at the home of Lord Harcourt in 1848. After dinner a small pumice-like stone was produced from a locket by the host and passed around the table. Before popping it into his mouth and swallowing it, Buckland remarked ‘I have eaten many strange things, but I have never eaten a king’s heart before.’ And so, a mummified portion of King Louis XIV of France came to be swallowed by an Englishman.

Leave a Reply