The Linnean Society is one of a number of learned societies that have made Burlington House their home. It was founded in 1788 by the amateur botanist Sir James Edward Smith who, spurred on by the President of the Royal Society, Sir Joseph Banks, purchased the natural history collection of the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus, who is known as the father of taxonomy – the classification and naming of biological organisms based on shared characteristics. This collection included Linnaeus’s correspondence, books and specimens and can be accessed as part of the society’s regular tours.

The Linnean Society received its Royal Charter in 1802 and as the oldest society dedicated to the study of natural history, it reaches out to a wide audience through education, its publications and many programmes which include current challenges of the natural world, such as biodiversity loss and climate change.

The Linnean Society of London. Photo Credit: © Linnean Society of London.

The Linnean Society of London. Photo Credit: © Linnean Society of London.

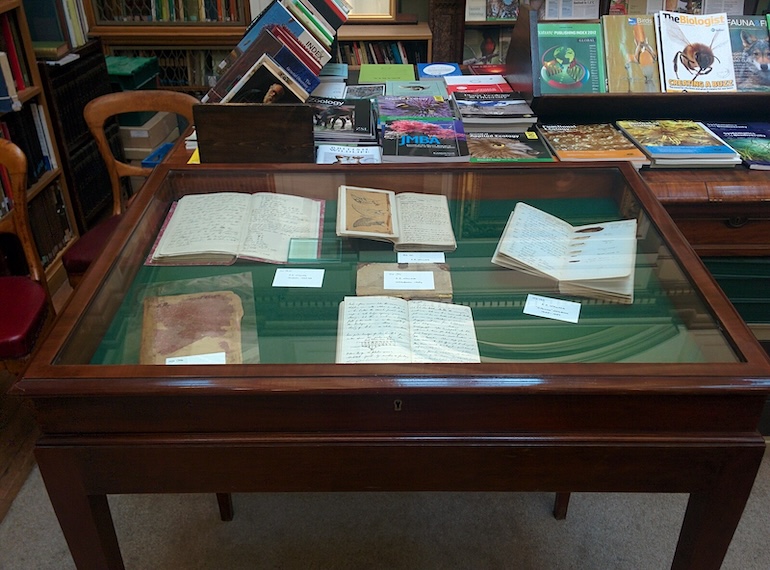

The society’s membership has featured many illustrious scientists, including its former president Robert Brown, who made contributions to the discovery of the cell nucleus; physician Edward Jenner, famous for his smallpox immunisation technique; biologist and anthropologist Thomas Huxley, whose many achievements include positing birds descended from theropod dinosaurs, and naturalist Sir David Attenborough. Unequivocally, the society’s most celebrated moment took place on 1 July 1858, when papers by Charles Darwin and Alfred Russell Wallace espousing their theories of evolution were read to a somewhat unresponsive audience. It was Wallace’s outline of his theory that finally spurred Darwin to make his research public after many years of working on his Theory of Evolution by Natural Selection. Notably, neither Darwin nor Wallace attended this meeting which was organised by the director of the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew, Joseph Dalton Hooker and Sir Charles Lyell, author of the ground-breaking Principles of Geology.

By the time these scientific geniuses were laying the groundwork of the new Victorian popular sciences, Linnaeus’s system had gained a strong following amongst natural historians worldwide. This success was aided by the rationalism of the French Revolutionaries in Paris who championed Linnaeus, as they obliterated the legacy of the Comte de Buffon, whose study of natural history was much broader in scope and understanding, having insightfully speculated about concepts of extinction and evolution at the dawn of the Ancien Regime’s collapse. In London, the Swedish naturalist Daniel Solander promoted the Linnaean system from his post as curator of the natural history collection of the British Museum. He went on to join that epic journey in the South Pacific aboard Captain James Cook’s Endeavour, alongside Joseph Banks.

Portrait of Carl Linnaeus, a Swedish biologist and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of Carl Linnaeus, a Swedish biologist and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Smith’s purchase and foundation of the Linnean Society in London cemented Linnaeus’s system over others, becoming an efficient and relatively simple method for naming species, hierarchically ranking them and placing them on genealogical trees. This system, published and revised by Carl Linnaeus in his Systema Naturea between 1735 and his death in 1778 popularised the use of a binomial system to name members of the animal, plant and mineral kingdoms. The first part refers to its genus and the second part names individual species. Our Great White Pelican friends at James’s Park were classified by Linnaeus as – Kingdom: Animalia; Class: Aves; Order: Pelecaniformes; Genus: Pelecanus; Species: P. Onocrotalus. This led him to name them Pelecanus Onocrotalus, a very western Latin name and Greek surname for a bird of African origin. These original five groupings have been greatly increased in number in modern times, with some taxonomists using up to twenty-two categories, including phylum, family, and subspecies.

Furthermore, our growing understanding of the complexity of life has placed the original three kingdoms under Domains, a higher taxonomic rank which comprises Archaea, Bacteria and Eukarya, the latter divided into kingdoms covering organisms with cells with a membrane- bound nucleus – fungi, animals, plants, seaweeds etc.

By modern standards, Linnaeus’s system of classification appears inadequate. He named just over 12,000 species of which 4,000 were animal. This is understandable as the system was designed to slot in new species as these were discovered. In contrast to Banks, Darwin and Wallace, Carl Linnaeus did not base his work on adventurous travels and field exploration but gathered his specimens through a network of international patrons and via his ‘apostles’ – young adventurers trained by the man himself and sent – many never to come back – to far flung exotic places around the globe. One such apostle was the previously mentioned Daniel Solander. The length and dangerous nature of these missions meant Linnaeus always had limited access to specimens, never mind ones that had not perished en route to Uppsala, where he held the rectorship of the university.

A display of Alfred Russel Wallace notebooks in the Linnean Society library. Photo Credit: © John Cummings via Wikimedia Commons.

A display of Alfred Russel Wallace notebooks in the Linnean Society library. Photo Credit: © John Cummings via Wikimedia Commons.

Nevertheless, Carl Linnaeus could have never envisaged that he was only observing an infinitesimal small sample of Earth’s life, as underpinning his vision was a staunch belief in the ‘fixity’ of life, the idea that all life is physically unchanged since the moment of Biblical Creation. More controversially, Linnaeus who coined the term homo sapiens, classified humans in four varieties: European, America, Asian and African. These he distinguished by racist stereotypes, foreshadowing racial and eugenic theory of the late 19th century.

Just like the British Museum reassessment of Sir Hans Sloane, the Linnaean Society has been forthcoming in addressing the darker legacy of Linnaeus’s ideas of race. Ultimately, the limited scope of the Linnaean system has seen it superseded by other classification system, chiefly amongst them cladistics which relies on grouping species under an ever growing tree of evolutionary life. Yet, despite these misgivings, Linnaean’s spirit survives in the still widely used binomial nomenclature. Linnaean-ism might not be fit for purpose in the 21st century’s study of the natural world, but it fulfils the most basic of linguistic needs: to name things.

The main library of the Linnean Society. Photo Credit: © John Cummings via Wikimedia Commons.

The main library of the Linnean Society. Photo Credit: © John Cummings via Wikimedia Commons.

Burlington House in London. Photo Credit: © Tony Hisgett via Wikimedia Commons.

Burlington House in London. Photo Credit: © Tony Hisgett via Wikimedia Commons.

Leave a Reply