Many who served on British ships in the age of sail were of African descent

Inspired by the “Black Greenwich Pensioners” exhibition that was held at Old Royal Naval College, my mind recently turned to Britain’s Black seafaring past, particularly to the time Britain was most actively involved in the Transatlantic Slave Trade and the enslavement of Africans, a time which loosely coincides with what we refer to as the Georgian age (1714-1837).

One of Britain’s earliest multicultural communities began – to borrow a phrase from Charles Dickens – “down by the docks”. An expanding British empire and growing international trade meant that by the mid-1700s, the maritime communities residing in East London’s port villages – Ratcliffe, Wapping, and Limehouse – were some of the most ethnically diverse in the country. Among the multitude of people living in these “Sailortowns” were Black sailors, some of whom were highly skilled Africans recruited or enslaved in their homelands to provide a substitute for British sailors who had died or deserted service. Others had been born into slavery in the Americas and were offered freedom in exchange for their service.

The adoption of African expertise in English and British matters relating to the sea can be dated back to at least the 16th century – the century in which Jacques Francis, an African salvage diver, took the lead in an attempt to recover the Mary Rose – King Henry VIII’s prized warship – that had sunk into the sea in 1545 during a battle with the French.

Remains and support structure for Mary Rose, King Henry VIII’s prized warship. Photo Credit: © Geni @ Wikimedia Commons.

Remains and support structure for Mary Rose, King Henry VIII’s prized warship. Photo Credit: © Geni @ Wikimedia Commons.

There was also a steady number of Black sailors serving on English ships throughout the 16th and 17th centuries. Sailors of African descent became a growing presence on board English (later British) naval and merchant vessels as a result of the increasing amount of trade and interaction between England and Africa that began in the mid-16th century; this included the slave trade.

As Britain’s involvement in the Transatlantic Slave Trade reached its zenith in the 18th century, the number of Black sailors serving on British ships grew, and as a result, so did the number of Black seafaring veterans. The new exhibition in Greenwich explores the lives of some of these veterans who became what was known as Greenwich Pensioners. The Greenwich Pensioners, all of them male, had served the Royal Navy and retired to live in the grandest building situated in the southeast London neighbourhood of Greenwich. The building was then known as the Royal Hospital for Seamen (today it’s usually referred to as the Old Royal Naval College*). It was a hospital, but not in the way we understand such institutions today. It was a place that provided hospitality to those in need. Life at this rather posh retirement home was very ordered and disciplined, with the residents being required to wear a uniform and perform daily chores. Residents who broke the rules were dubbed “canaries” and made to wear a yellow coat and carry out menial jobs. It wasn’t all bad, though, as residents were also entitled to three pints of beer a day!

Old Royal Naval College in Greenwich, London. Photo Credit: © Ursula Petula Barzey.

Old Royal Naval College in Greenwich, London. Photo Credit: © Ursula Petula Barzey.

* The naval college occupied the former hospital buildings between 1873 and 1998, though the name has stuck. Today the buildings are part tourist attraction, part film location and home to the University of Greenwich and Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance.

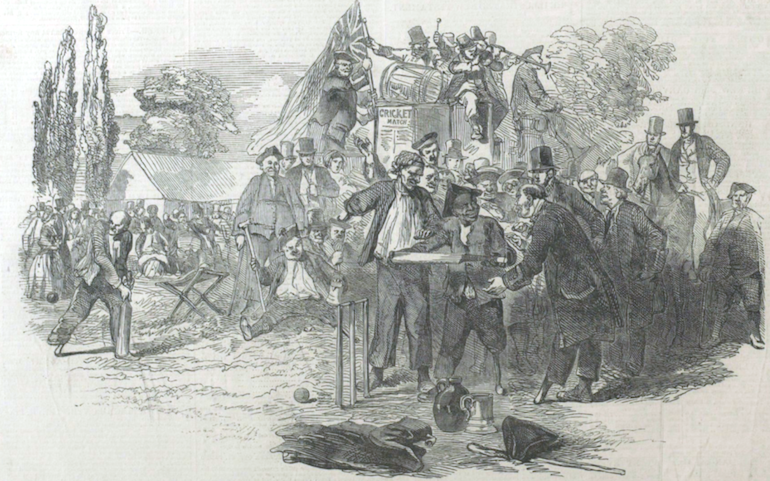

Many of the pensioners at Greenwich had been injured in dangerous and deadly sea battles and had disabilities. This wasn’t to stop them, and thus began the tradition of one-armed vs one-legged cricket, with one team made up of players missing an arm and the other with players missing a leg. Drawings from the time clearly show that Black and white Greenwich pensioners enjoyed the game, with matches played all over London.

Greenwich Pensioners’ Cricket Match, at the Priory Ground, near Lewisham, 1848. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Greenwich Pensioners’ Cricket Match, at the Priory Ground, near Lewisham, 1848. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Relatively speaking, not much is known about the Black pensioners of Greenwich Hospital, and work is still being done to discover more details. We do know a few of their names, however, including a man called Briton Hammon.

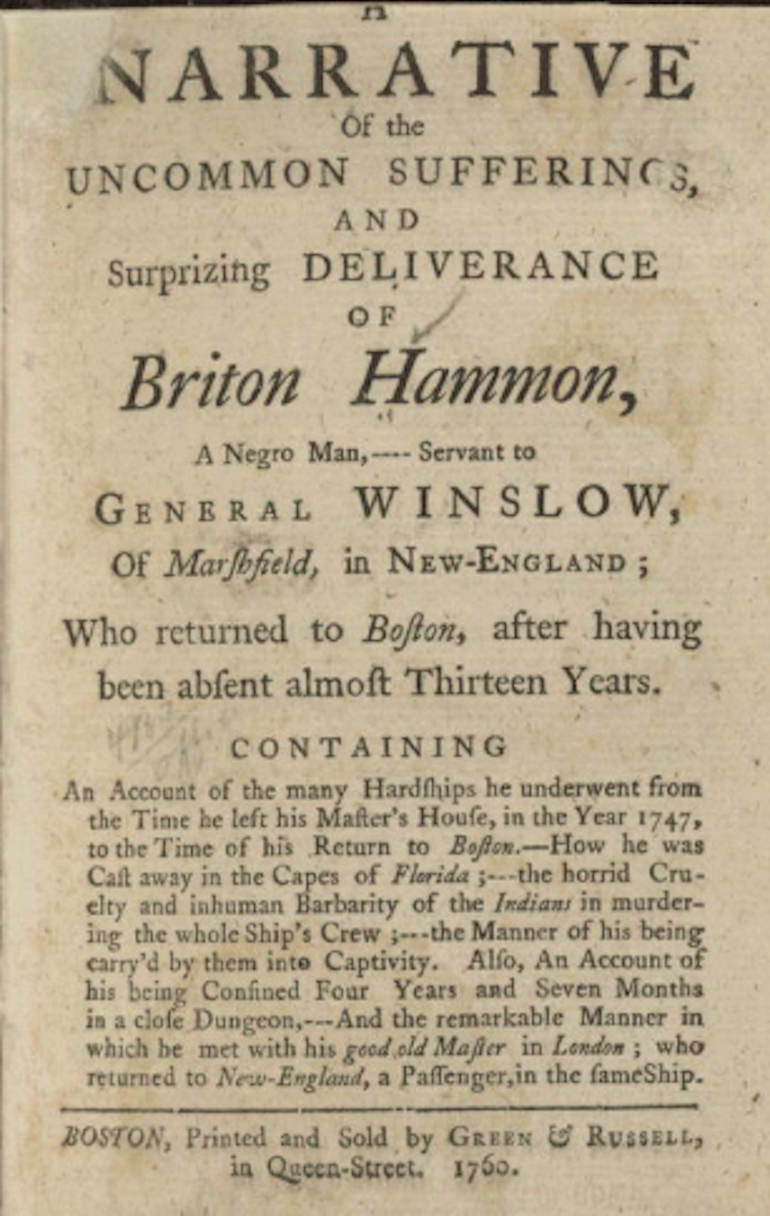

Briton Hammon is believed to have been an enslaved African American man who, in the mid-1700s, was given permission by his Massachusetts slaveholder to embark on a trading voyage to Jamaica. On its way back from the island, the ship was wrecked off the coast of Florida, and with the exception of Hammon, the entire crew was captured and killed by locals. He was later rescued, sold to the governor of Cuba, and imprisoned for refusing service on a Spanish warship. Hammon eventually managed to escape his confinement by jumping onto a British naval ship on which he served and was injured during the Seven Years’ War. He ended up at Greenwich Hospital to recover and later supposedly reunited with his enslaver on his way back to Massachusetts.

We know these things about Hammon due to an autobiographical narrative, though some scholars think it was subject to heavy editorial interference. Work is still being done to unravel the full and complete story of Britton Hammon.

Narrative of Briton Hammon. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Narrative of Briton Hammon. Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Another Black sailor who served in the Royal Navy is depicted on one of London’s most well-known landmarks, Nelson’s column. This monument commemorates Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson and the British victory at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. The battle is considered one of the most significant in British history as it put paid to an invasion attempt on Britain by Emperor Napoleon of France. And Black men were part of the victorious crew working right across the fleet of 27 ships that Nelson commanded at the battle. It is known that there were at least 10 men of African descent on board the HMS Victory – Nelson’s flagship at the battle where he lost his life.

On the south face of the plinth that supports the column is a bronze relief called “The Death of Nelson at Trafalgar.” On it appears the likeness of a sailor believed to be the African-born George Ryan, who was recruited into the navy in West Africa in his early 20s. He’s shown holding a musket and looking up into the ship rigging to spot the French sniper who has just shot and mortally wounded Nelson.

Black sailor depicted with a musket on the left of the base of Nelson’s Column in Trafalgar Square, London. Photo Credit: © Ursula Petula Barzey.

Black sailor depicted with a musket on the left of the base of Nelson’s Column in Trafalgar Square, London. Photo Credit: © Ursula Petula Barzey.

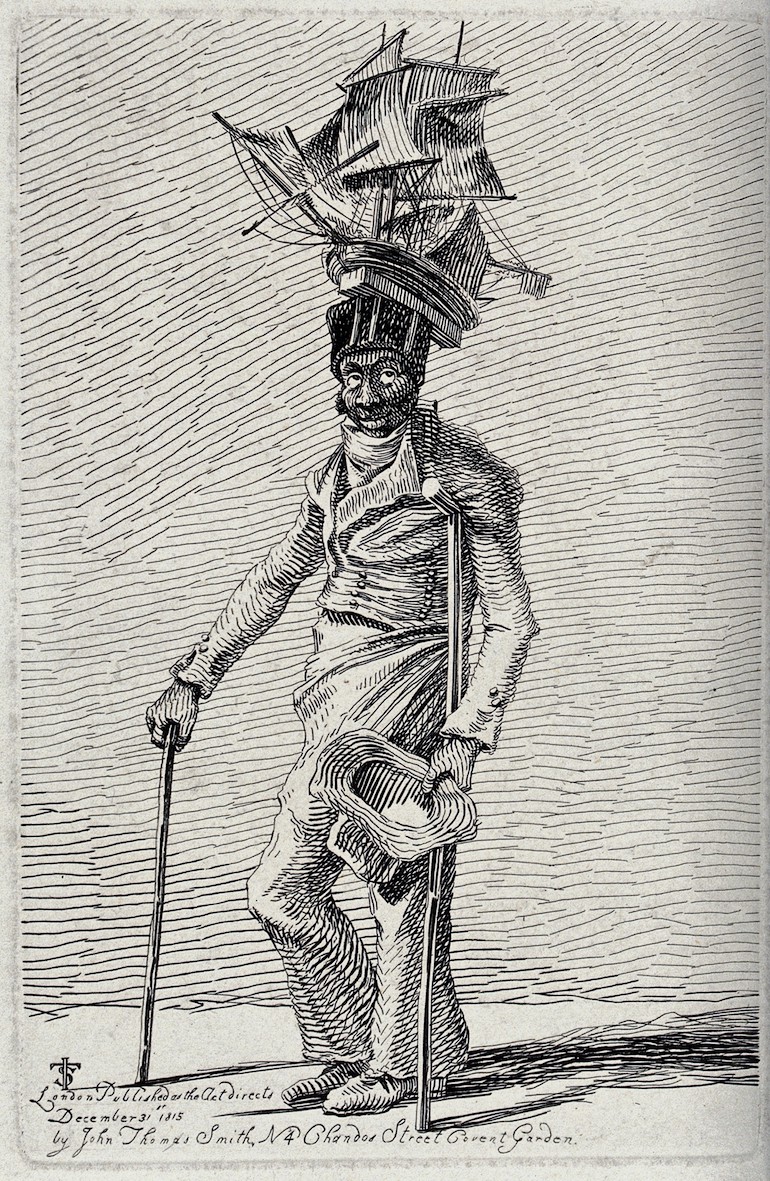

Not all injured or retired seamen were given the dignity of a pension or a retirement home at Greenwich. Many were effectively left to fend for themselves when age or injuries in the line of duty rendered them unable to work. Such was the case with Joseph Johnson, who was discharged from the Merchant Navy after he’d been wounded and disabled. He was subsequently denied any welfare on the grounds that he worked in the merchants’ service. In London, racial prejudice and his disability meant economic opportunities were very hard to come by and so, like many others, he resorted to begging. Johnson, clearly very enterprising, created the model of a ship which he placed on the top of his hat and developed a performance routine for passing members of the public in the Tower Hill area and other places close to London. It is said that he was able to replicate the motion of the ship sailing on the sea by bending and swaying his head, all whilst singing popular sea shanties!

Sailor Joseph Johnson in ragged clothes moving with the aid of crutches. Photo Credit: © Wellcome Library via Wikimedia Commons.

Sailor Joseph Johnson in ragged clothes moving with the aid of crutches. Photo Credit: © Wellcome Library via Wikimedia Commons.

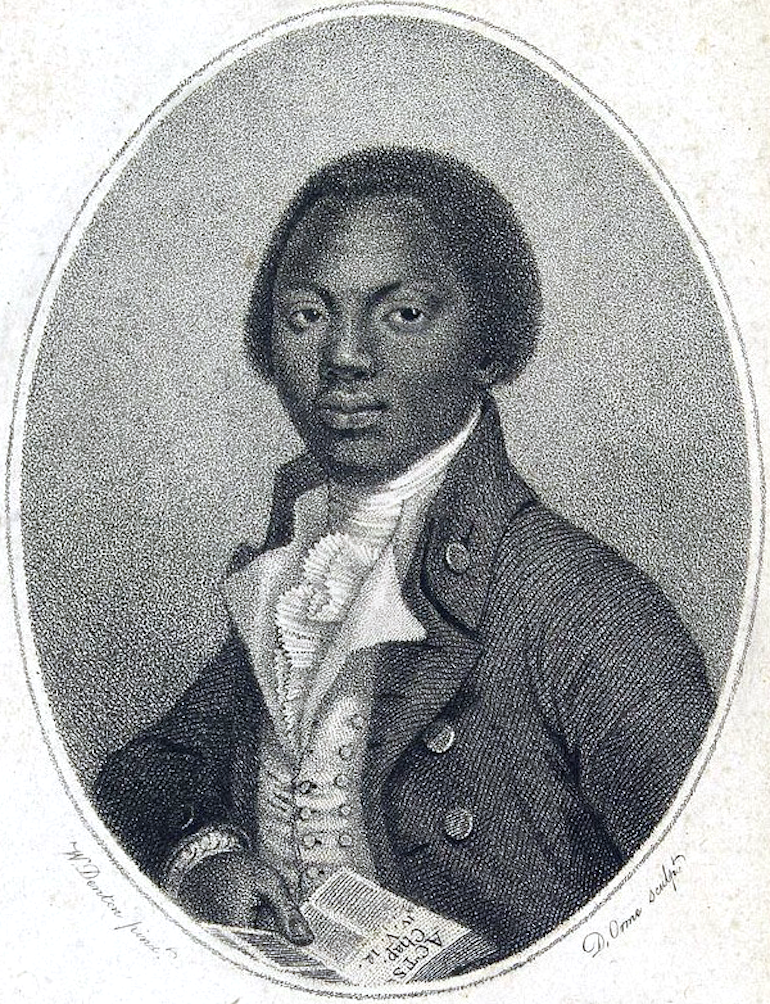

Perhaps, Britain’s most famous Black sailor of the Georgian age was Olaudah Equiano, a remarkable figure who lived a remarkable life. He was born in Igboland in what is today southeastern Nigeria. As a young boy, around 11, he was captured and enslaved, separated from his family and sold into slavery in the Americas. Equiano would be sold and resold a number of times. One of his enslavers was a Royal Naval lieutenant, Michael Pascal, with whom he served for several years during the Seven Years’ War. In between his spells at sea, Equiano was put into the care of two sisters known as the Guerins – who lived in Greenwich.

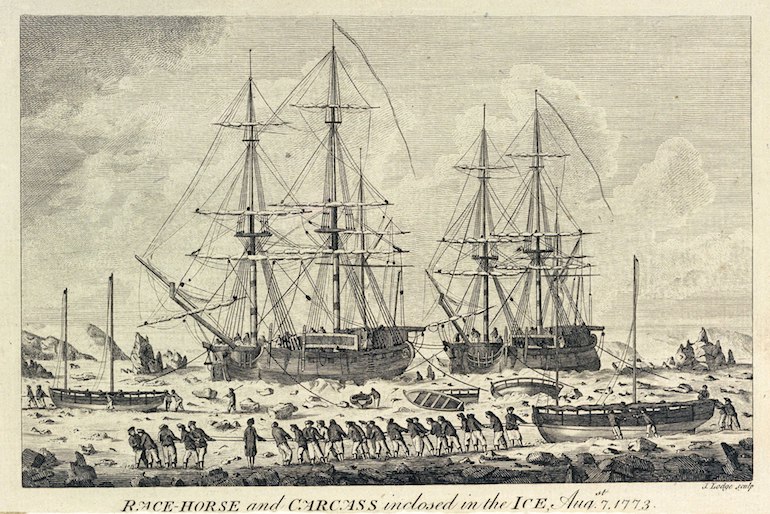

Equiano was sold once again but was eventually able to buy his freedom for the price that had been paid for him. He settled in England before going back to a life of seafaring, this time as a free man. One of his seafaring adventures was as part of the Phipps expedition to the Arctic to find a northeast passage to Asia. Two vessels made up the mission – the HMS Racehorse and HMS Carcass – which departed from Deptford, southeast London, in 1773. Equiano served on the Racehorse. Onboard the same ship, was a 14-year-old Horatio Nelson. It was not a successful mission as the two ships got caught up in ice after a couple of months and the expedition was ultimately abandoned.

HMS Carcass (1759). Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

HMS Carcass (1759). Photo Credit: © Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

As a free man in London, Equiano became a staunch slave trade abolitionist and wrote an enormously influential book about his life and experience of being enslaved. It is called “The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano or Gustavus Vassa the African.” In the book, which became a bestseller and was printed nine times whilst he was still alive, Equiano recounts his horrific experiences of being shipped to the Americas and his various adventures at sea – including seeing polar bears, walruses, and never-ending daylight at the North Pole.

From the Greenwich Pensioners to Equiano, more is being discovered about London’s Black mariners all the time. Their fascinating stories reveal the complex, rich, diverse history of the capital and Britain’s long seafaring past. They will lead you on a journey across many different parts of the city. So what are you waiting for? All aboard!

Two vessels made up the mission – the HMS Racehorse and HMS Carcass – which departed from Deptford, southeast London, in 1773. Equiano served on the Racehorse. Onboard the same ship was a 14-year-old Horatio Nelson. It was not a successful mission as the two ships got caught up in ice after a couple of months, and the expedition was ultimately abandoned.

Olaudah Equiano, aka Gustavus Vassa. Photo Credit: © Unknown Artist via Wikimedia Commons.

Olaudah Equiano, aka Gustavus Vassa. Photo Credit: © Unknown Artist via Wikimedia Commons.

Leave a Reply