The Waste Land by Thomas Stearns Eliot (T. S. Eliot), who came from the United States but lived in England, is often called the greatest poem of the twentieth century. Its 433 lines depict the London of 1923 in the fragmented form of an abstract painting. Scenes appear like shapes without title or outline. To celebrate the centenary of the poem, I have devised a walk through The City connecting locations mentioned by Eliot. The Waste Land was published as a single entity by Virginia and Leonard Woolf’s Hogarth Press as T.S. Eliot was associated with the artistic intellectuals of The Bloomsbury Group.

The Waste Land And Other Poems by T.S. Eliot. Photo Credit: © Rick Jones.

The Waste Land And Other Poems by T.S. Eliot. Photo Credit: © Rick Jones.

This music crept by me upon the waters

along the Strand, up Queen Victoria Street…

We begin at Blackfriars Underground Station and, as the poem says, go up Queen Victoria Street, wafted hence by snatches of music – ragtime, Wagner’s Rhinemaidens, a typist’s gramophone record. T.S. Eliot was born in St Louis, Missouri beside the Mississippi and felt at home by the River Thames – though water is death in the poem as well as comfort. The Strand is not the street of that name but the beach curving with the river from Embankment to Temple.

O o o o that Shakespeherian rag

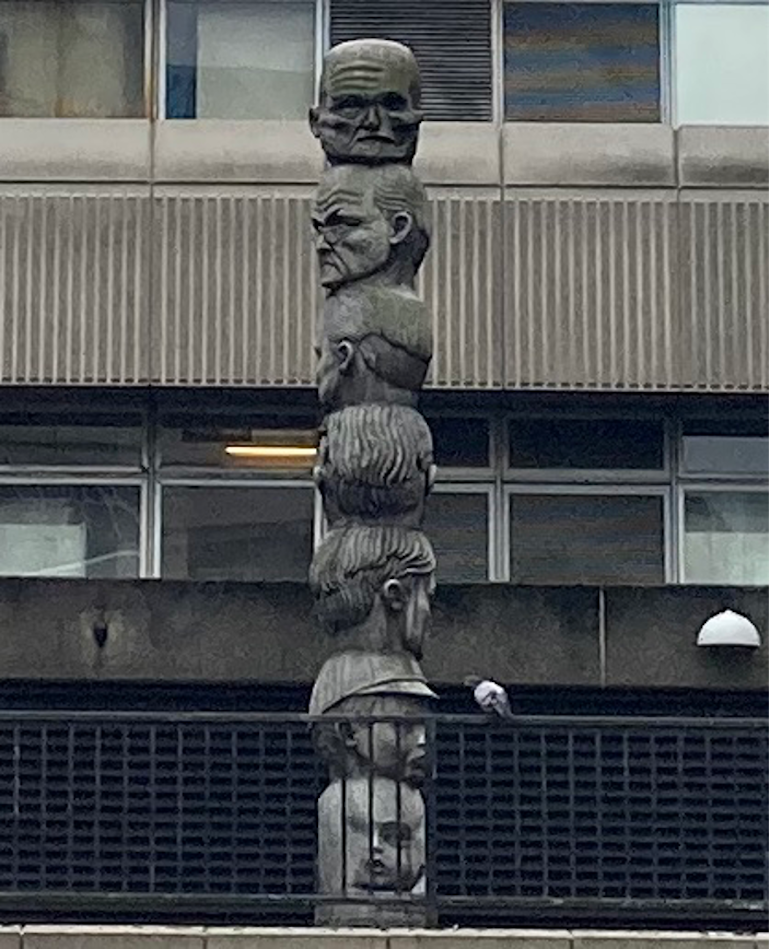

First stop: Baynard House and the Shakespeare ‘Seven Ages’ totem pole. As a student, T.S. Eliot devoured literature of all cultures and ages, and The Waste Land is rich with quotations, not least from the bard.

Seven Ages of Man statue referenced in The Waste Land poem by T.S. Eliot. Photo Credit: © Rick Jones.

Seven Ages of Man statue referenced in The Waste Land poem by T.S. Eliot. Photo Credit: © Rick Jones.

Those are pearls that were his eyes

Eliot quotes from The Tempest in response to the clairvoyant turning up the Tarot’s drowned sailor with his white eyes.

….to luncheon at the Cannon Street Hotel

followed by a weekend at the Metropole

Eliot worked in the Colonial and Foreign Department of Lloyds Bank in Threadneedle Street from 1917 to 1927. Business customers came to him fresh from the ship, and Mr. Eugenides, a Smyrna merchant, chatted up a secretary with the above invitation. The Cannon Street Hotel was sleazy and never full. The Metropole was on Trafalgar Square and attracted a classier clientele.

a crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many,

I had not thought death had undone so many.

Sighs short and infrequent were exhaled

and each man fixed his eyes before his feet

flowed up the hill and down King William Street

to where St Mary Woolnoth kept the hours

with a dead sound on the final stroke of nine

Working backward through the text, the stumpy baroque church of St. Mary Woolnoth is the only edifice in the City of London by Nicholas Hawksmoor, the architect. He worked with Christopher Wren on St Paul’s Cathedral. Although Eliot’s automaton workforce clock-watched more apprehensively than today’s flexitime drones, the clock keeps the hours. The King William of the street is William the Third, the Dutchman. It is no coincidence that the Bank of England, which was founded in his reign, was modelled on the Bank of Amsterdam.

St Mary Woolnoth, Anglican church in the City of London referenced in The Waste Land poem by T.S. Eliot. Photo Credit: © Rick Jones.

St Mary Woolnoth, Anglican church in the City of London referenced in The Waste Land poem by T.S. Eliot. Photo Credit: © Rick Jones.

O City city I can sometimes hear

beside a public bar on Lower Thames Street

the pleasant whining of a mandoline

the clatter and the chatter from within

where fishmen lounge at noon…

Strains of music emerge from a fish trader’s pub, probably The Walrus and Carpenter opposite old Billingsgate, the former fish market which is now a conference centre. The war casts a shadow as the women discuss their anxieties with their men demobbed while the landlord calls ‘Time!’ like the Grim Reaper.

…and where the walls

of Magnus Martyr hold

inexplicable splendour of Ionian white and gold.

Eliot is stunned into silence by the unexpected beauty of Magnus Martyr’s interior. The Reverend Fynes-Clinton was new at the church in 1921 and an ardent Anglo-Catholic. From this time, Eliot developed a preference for that type of English-language Christianity which was simply a translation of the Latin Church after the reformation. This was in contrast to the Unitarian faith of his parents, which was Christian but without accepting the divinity of Christ – unitarian, not trinitarian.

St Magnus Martyr is open most weekdays and worth visiting for its beautiful miniature model of London Bridge in Shakespeare’s time. We now ascend to the bridge for the final stop.

the barges wash

drifting logs

down Greenwich Reach

to the Isle of Dogs

weialala leia

wallala leialala

Looking east over the bridge, there are barges and tugs and the battleship HMS Belfast, which was not there in Eliot’s time. In the distance, the grey metal-and-glass skyscrapers of Docklands mark the Isle of Dogs and the river reaching south to Royal Greenwich. Weialala sing Woglinde, Wellgunde, and Flosshilde from Wagner’s The Ring in the depths of the Rhine, masquerading as the River Thames. Eliot imparts a sense of the operatic epic in this patchwork view of the mighty but desolate city.

London Bridge is referenced in The Waste Land poem by T.S. Eliot. Photo Credit: © Rick Jones.

London Bridge is referenced in The Waste Land poem by T.S. Eliot. Photo Credit: © Rick Jones.

Leave a Reply