Let me take you back to the Britain of 1951. The Second World War had ended just six years earlier. London, like many other British cities, had been bombed relentlessly and still bore the scars of the Blitz. Surviving buildings were covered in layers of dark sooty dust and rationing was still the order of the day and, for fresh meat, remained in place until 1954.

Then the Festival of Britain opened on 4 May 1951 to give the country a morale boost. It celebrated Britain’s contribution to civilization – past, present and future. The arts, science, industrial design and technology took centre stage. The Festival of Britain was a vision of the future. It pointed the way to new and healthier ways of living for a nation that had sacrificed so much in the fight against fascism.

The Festival of Britain marked a watershed in British history. Just nine years earlier in 1941, the Battle of El Alamein marked the first turning point in the Second World War. Ten years later, a band called the Beatles were wowing audiences in Hamburg. The British Empire was shrinking and people from across that empire were seeking a new life in the United Kingdom.

Festival of Britain – Remembering a Brave New World. Photo Credit: © Compilation by Antony Robbins.

Festival of Britain – Remembering a Brave New World. Photo Credit: © Compilation by Antony Robbins.

Badged guiding also started at around this time, with the first London guides qualifying in 1950/1951. The first badge for qualified London guides was red, the colour of London. Today it is blue and the badge is the proud symbol of all qualified London Blue Badge Tourist Guides.

The Festival of Britain was initially conceived to mark the centenary of the 1851 Great Exhibition. Rather than staging another World Fair, it became a celebration of peace and modernity. Its champion was Labour politician and former leader of the London County Council, Herbert Morrison, grandfather of New Labour supremo Peter Mandelson.

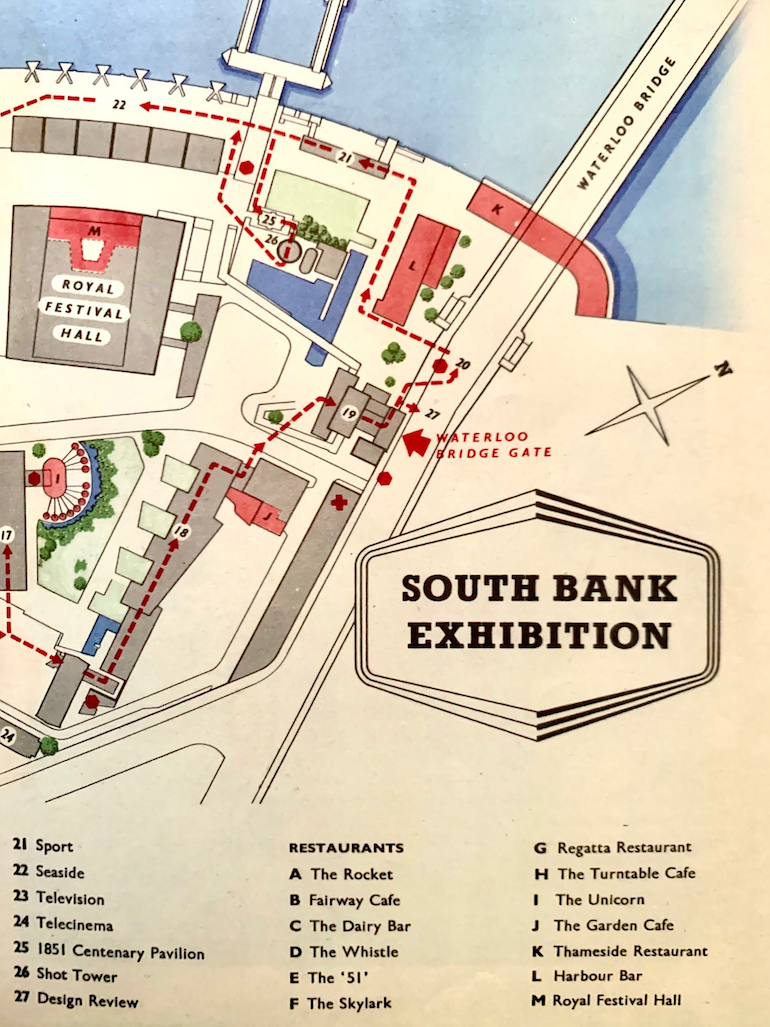

Today, when we think of the Festival of Britain, we picture the transformation of the twenty-seven acre South Bank site, which attracted over nine million people. Its Dome of Discovery and space-rocket-like Skylon sculpture were instant hits. People travelled across the United Kingdom to see the spectacle, some bedding down overnight in Clapham’s Second World War-era deep-level bomb shelters.

The Festival of Britain was actually a nationwide event. Belfast held the Farm and Factories exhibition. Glasgow’s Kelvingrove hosted the Industrial Power exhibition. There was even a festival ship, HMS Compania, which visited ten United Kingdom ports. This 1941 converted aircraft carrier escort had begun life transporting refrigerated New Zealand lamb.

London’s additional Festival of Britain sites included Battersea Park, which hosted pleasure gardens, and South Kensington, home to the science exhibition. On Poplar’s Balfron Estate, architect Frank Gebbard conceived the Living Architecture Exhibition. Although it was designed as an ambitious example of post-war renewal, it failed to draw the crowds and was considered by many to be too much of a muddy building site to appeal to 1950s sensibilities.

Festival of Britain – Costain delivered on time. Photo Credit: © HM Stationery Office.

Festival of Britain – Costain delivered on time. Photo Credit: © HM Stationery Office.

The Festival of Britain spotlighted some of the UK’s rising stars. They included its designer, Abram Games, the graphic artist who had been responsible for many of the nation’s wartime propaganda posters. His Jewish faith and socialist values inspired him to create some of the twentieth century’s most memorable graphic design. The Festival of Britain’s architect, Hampstead-born Sir Hugh Casson, became the future President of the Royal Academy. Aged just thirty-six at the time, Casson hired the best young talents of the day.

Some of the Festival’s distinct designs, seen on textiles and furniture, were inspired by science. The work of Nobel Prize-winning scientist Dorothy Hodgkin featured prominently. She was the pioneer of X-Ray crystallography. This revealed the molecular structure of compounds and chemicals … and made for brilliant designs.

If the Festival of Britain were held today, it would be supported by an array of sponsors. In 1951 however, apart from Guinness, who funded the Battersea pleasure gardens, private money was largely absent. Motor industry giants like Morris and Rover, for example, contributed nothing to the Festival’s £12,000 budget.

Also absent was any celebrity endorsement. Hit films in 1951 included Pool of London, staring Earl Cameron, one of Britain’s first black celebrities. Cameron’s endorsement, and that of other leading lights of the day like Alec Guinness, Joan Greenwood and Noel Coward, was not sought to add stardust to the proceedings.

However, ordinary British people loved the Festival of Britain. It gave them a taste of contemporary living. The South Bank boasted six restaurants at a time when you struggled to get a cup of coffee in museums and galleries. It had outdoor terraces where you could watch the world go by – an early British experience of café society.

The South Bank Festival of Britain site had 13 restaurants. Photo Credit: © HM Stationery Office.

The South Bank Festival of Britain site had 13 restaurants. Photo Credit: © HM Stationery Office.

Not everyone embraced the Festival of Britain. Winston Churchill returned to government in 1951 but he was keen to see the back of the Festival of Britain, which he saw as a celebration of socialism. For most visitors, however, it was something fresh and modern and helped to lift the nation out of the greyness of post-war Britain.

World War Two was itself a catalyst for innovation. It marked the dawn of a new era. From trauma and destruction emerged technological know-how and innovation. This included advances in design for everyday living, which the nation was excited to embrace and which the Festival was equally keen to spotlight.

Let us hope that the Festival of Britain’s seventieth anniversary will help us all to look to a more optimistic future, just as we did back in 1951.

Leave a Reply