Westminster Abbey is definitely one of London’s must-see attractions. And you’re sure to discover new things every time you visit, especially if you go with a knowledgeable Blue Badge Tourist Guide.

Among other things, the Abbey is the burial site of many of the most famous people in British history. These include the so-called father of English literature and author of The Canterbury Tales, Geoffrey Chaucer, as well as the writer Charles Dickens. Shakespearean hero Henry V and the scientist Isaac Newton are here too. In fact, more than 3,500 people are buried or memorialized in Westminster Abbey.

But for the most part, they are men.

So in this article, we explore the stories behind some of the notable women in Westminster Abbey.

The 18th Century West Front of Westminster Abbey, by Nicholas Hawsmoor. Photo Credit: © Antony Robbins.

The 18th Century West Front of Westminster Abbey, by Nicholas Hawsmoor. Photo Credit: © Antony Robbins.

The Virgin Queen

We’ll start with the so-called Virgin Queen, Elizabeth I, who died in 1603. Elizabeth’s 44-year reign has been called a golden age of British history.

The daughter of Henry VIII and his second wife, Anne Boleyn, Elizabeth saw off the Spanish Armada in 1588 and encouraged the exploration of new lands. Art and culture flourished during this era – the time of William Shakespeare and Christopher Marlowe, among others.

She was England’s second female monarch, succeeding her older half-sister, Mary 1, whom we’ll talk about next.

Elizabeth never married and had no children, so her death at age 69 marked the end of the Tudor dynasty.

Bloody Mary

Elizabeth’s coffin rests right on top of her sister’s, although only Elizabeth has an effigy. The two women (one Protestant, the other Catholic) were divided in life but are united in death.

Mary was the only surviving child of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon – the first of his eventual six wives. Mary took the throne after the brief reign of her half-brother, Edward VI (Henry’s child with his third wife, Jane Seymour. Keeping up?)

Mary was determined to reassert her mother’s Catholic faith over England. Henry VIII had broken away from the authority of the Pope and founded the Church of England after failing to obtain an annulment from Rome of his first marriage. Now under his own authority, Henry was free to marry his new love, Anne (although she soon fell out of favor too and was beheaded at the Tower of London).

England’s first queen in her own right married Philip II of Spain. Mary ruled for only five years before dying childless in 1558. But during that time, she had 280 people burned at the stake for their Protestant faith, and in so doing developed the nickname, Bloody Mary. It’s arguable whether that’s a fair moniker, given that her father had about 8,000 people killed and is simply called Henry VIII.

The statues of 21st-century Christian martyrs on the Abbey’s West Front. Photo Credit: © Antony Robbins.

The statues of 21st-century Christian martyrs on the Abbey’s West Front. Photo Credit: © Antony Robbins.

Anne of Cleves

Henry VIII’s 4th wife has a modest grave marker by the area in the Abbey known as Poets’ Corner.

She was 24 when she married the 48-year-old king in 1540. Henry decided to marry Anne after seeing a portrait of her by the court painter Hans Holbein. He was disappointed with the real woman, though.

When the couple eventually met, the King wasn’t attracted to her. The marriage was annulled after six months. Although you might be tempted to feel sorry for Anne, compared with the fate of Henry’s other wives, she actually got a pretty good deal.

The Queen’s cousin

We’ll now talk about three notable women who are buried in the south aisle of Westminster Abbey’s Lady Chapel. The first, Mary Queen of Scots, was the daughter of James V of Scotland and cousin to Elizabeth I. A devout Catholic and a rival claimant to the English throne, Mary was a threat to Elizabeth and was executed in 1587. In one of the great ironies of British history, Mary’s son, James, succeeded Elizabeth on the throne after she died childless.

The Chapter House at Westminster Abbey in London. This is where Parliament, presided over by the king, first met. It was badly damaged during WW2. Photo Credit: © Antony Robbins.

The Chapter House at Westminster Abbey in London. This is where Parliament, presided over by the king, first met. It was badly damaged during WW2. Photo Credit: © Antony Robbins.

The mother-in-law

Buried next to Mary is Margaret, the beautiful Countess of Lennox. Margaret’s tomb depicts her children, including Lord Darnley, the second husband of Mary Queen of Scots and father of James 1.

The kingmaking matriarch

Lady Margaret Beaufort, the matriarch of the Tudor dynasty, was buried here in 1509. Margaret was Henry VIII’s ambitious paternal grandmother, and she consolidated her family’s grasp on the throne. Her son, Henry VII, is buried in the Lady Chapel with his wife, Elizabeth of York. Margaret founded two Cambridge colleges and was a patron of England’s first printer, William Caxton. Her tomb is by the Italian artist Pietro Torrigiano. The tempestuous Renaissance sculptor undertook the commission in England while on the run from Italy – having punched his Florentine contemporary, Michelangelo.

Chapel of Henry VII (Lady Chapel) at Westminster Abbey. Photo Credit: © Ursula Petula Barzey.

Chapel of Henry VII (Lady Chapel) at Westminster Abbey. Photo Credit: © Ursula Petula Barzey.

The Grim Reaper

Lady Elizabeth Nightingale died in childbirth in 1731. Her tomb is probably the scariest in Westminster Abbey. If you enjoyed the 2005 movie Amityville Horror, you’ll love this 1761 sculpture by French stonemason LF Roubiliac. It depicts a skeletal Grim Reaper emerging from what looks like a fireplace to spear the dying woman with a long dart. Elizabeth’s distraught husband, Joseph, fights in vain to save his wife as she fades away in his despairing embrace.

The poetry and the pleasure

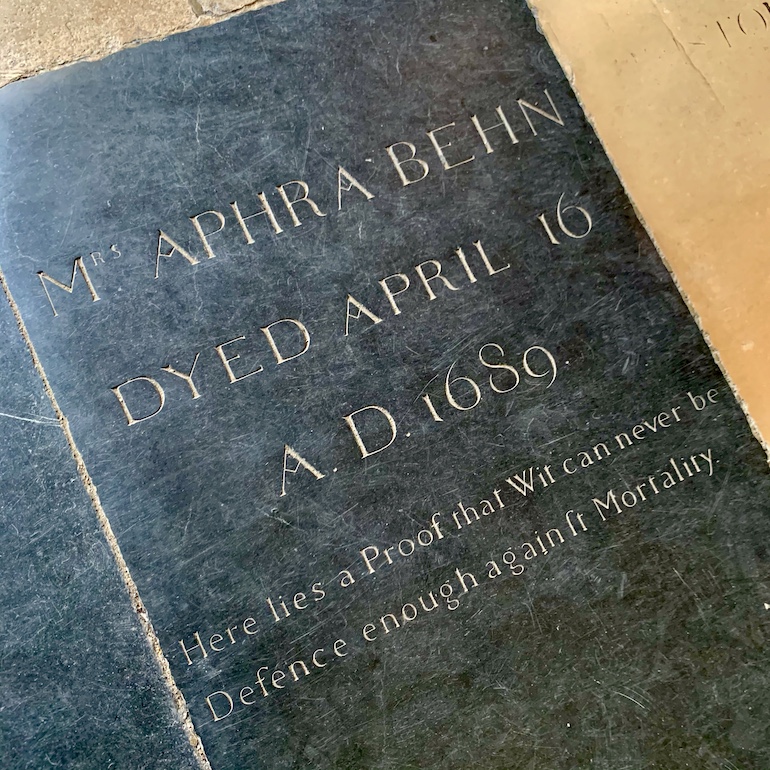

As we leave the Abbey, we pay our respects to England’s first professional female playwright, Aphra Behn, in the east cloister. Behn was one of the most successful writers of the 17th-century Restoration era when the theatre-loving Charles II – the so-called Merry Monarch – returned from exile to take back the throne following England’s 11-year experiment as a republic.

The grave of Aphra Behn. England’s first professional female writer was regarded as being rather racy in her day. Photo Credit: © Antony Robbins.

The grave of Aphra Behn. England’s first professional female writer was regarded as being rather racy in her day. Photo Credit: © Antony Robbins.

Behn wrote Oroonoko, the 1688 story of an enslaved African prince. She was part of a rakish group of writers including John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester – portrayed on screen by Johnny Depp in 2004’s The Libertine. Like Rochester, Behn dedicated her life to poetry and pleasure and was considered rather scandalous. The inscription on her gravestone reads: ‘Here lies a Proof that Wit can never be Defence enough against Mortality.’

Leave a Reply