The recent release of the Winston Churchill movie, Darkest Hour has brought one of London’s most popular tourist attractions into even sharper focus. The movie, in which Gary Oldman brilliantly captures the look, mannerisms and voice of Britain’s great wartime leader, is largely set in the Churchill War Rooms. However the rooms were not used as the location for the movie. I imagine the space would have been far too cramped and so studio sets were built. And they are incredibly accurate. Having spent much time in the Churchill War Rooms, the magic of the movies credibly conveys an accurate representation of how these vital rooms appeared then and now.

Churchill War Rooms – New Entrance. Photo credit: © Imperial War Museum.

Churchill War Rooms – New Entrance. Photo credit: © Imperial War Museum.

With the rise of Hitler and Nazi Germany, It was essential that a secure and safe space was found from which the country could be run in the event of full scale war breaking out. The job of identifying and then equipping and preparing such a space fell to senior military officer, General Hastings Ismay (affectionately addressed by Churchill as “Pug”. Have a look at his photograph and you’ll understand why). With supreme military efficiency, Ismay set about his task and by May 1938, he had identified the space and by September of the same year, the rooms were ready for use. A year later, Britain was at War and the War Rooms came into immediate use.

The War Rooms, originally known as the Cabinet War Rooms were created out of the basement space underneath the “New Public Offices”. These buildings now house the Treasury and the Department for Media, Culture and Sport. Importantly, the buildings were constructed with a very strong steel frame and it was believed that this would afford an enhanced level of protection to staff. In the event this turned out to be very far from the truth. Even with the addition of further strengthening above the War Rooms, it would not have been able to withstand a direct hit from a high explosive bomb.

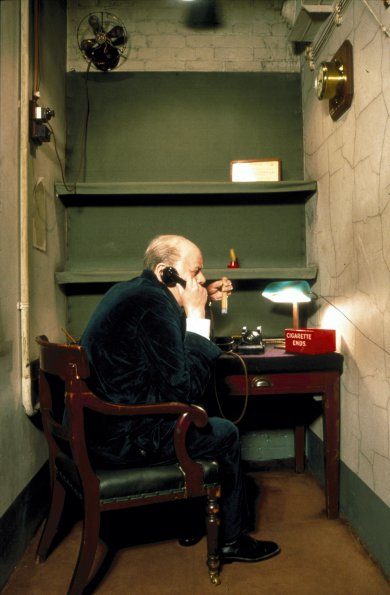

Churchill War Rooms – Churchill in Transatlantic Telephone Room. Photo credit: © Imperial War Museum.

Churchill War Rooms – Churchill in Transatlantic Telephone Room. Photo credit: © Imperial War Museum.

Neville Chamberlain had been engaging with the Nazi regime in an attempt to get a peace deal with Hitler. His famous return from Berlin with a document signed by Hitler that he declared to mean “peace for our time” proved to be nothing of the kind. Despite much support, the appeasement policy that Chamberlain pursued ultimately proved to be a failure. Churchill always maintained that Hitler was great threat and so it proved. By May 1940 Chamberlain was out of office.

Following the resignation of Chamberlain and Churchill’s rise to the Premiership, the War Rooms became the focus of Political and Military decision making with the Chiefs of Staff and the War Cabinet working adjacent to each other in what seems to us to be a ridiculously confined space. It is hard to believe that Britain’s war effort could be directed from the cramped and restricted spaces we see today. For the younger generation the idea that none of those objects of the digital age, I phones, computers,TVs, that we take for granted, existed. This was an analogue war conducted using telephones, maps, drawing pins and bits of string.

The Churchill War Rooms should be on every visitor to London’s list. To see the tiny room where Churchill spoke on the first transatlantic hotline to Roosevelt, is extraordinary. There is also a fascinating museum devoted to Churchill containing a wealth of artefacts including a selection of his decorations and medals, his beautiful (and priceless) pocket watch and even the famous door from Number 10 Downing Street.

Churchill War Room – The Map Room. Photo credit: © Imperial War Museum.

Churchill War Room – The Map Room. Photo credit: © Imperial War Museum.

There is also an Enigma Machine, on display. This was the Nazi coding machine that sent encrypted messages from the High Command to German military assets. Intercepting and decoding these messages was a top priority for Churchill. With the brilliant minds deployed at Bletchley Park, led by mathematical genius, Alan Turing, brilliantly depicted in the movie, The Imitation Game, the code was cracked, building on the work of earlier Polish Intelligence. It has often been claimed that the work completed on Enigma at Bletchley shortened the war by 2 years and saved possibly hundreds of thousands of lives.

Go and see “Darkest Hour” and then book your visit to the Churchill War Rooms. A Blue Badge Tourist Guide will help bring this fascinating place to life with stories of what it was like to work down here during the war where the spirit of Churchill was and is ever-present. I have a feeling this site will be busier than ever this year.

IMPORTANT NOTICE

As a result of the awarding winning film ‘The Darkest Hour’ starring Gary Oldman who won an Oscar for Best Actor 2018, the Churchill War Rooms are experiencing a high demand for admission tickets. When planning your trip to London, to avoid disappointment, it is advisable to secure your admission tickets in advance.

Leave a Reply