London has (or had) a reputation for housing members of the international awkward squad. One exile was the French writer Émile Zola who arrived at Victoria Station on 19 July 1898 without any luggage or knowledge of the English language. He spent his first night at the Grosvenor Hotel and later moved to the more modest Queen’s Hotel in Norwood.

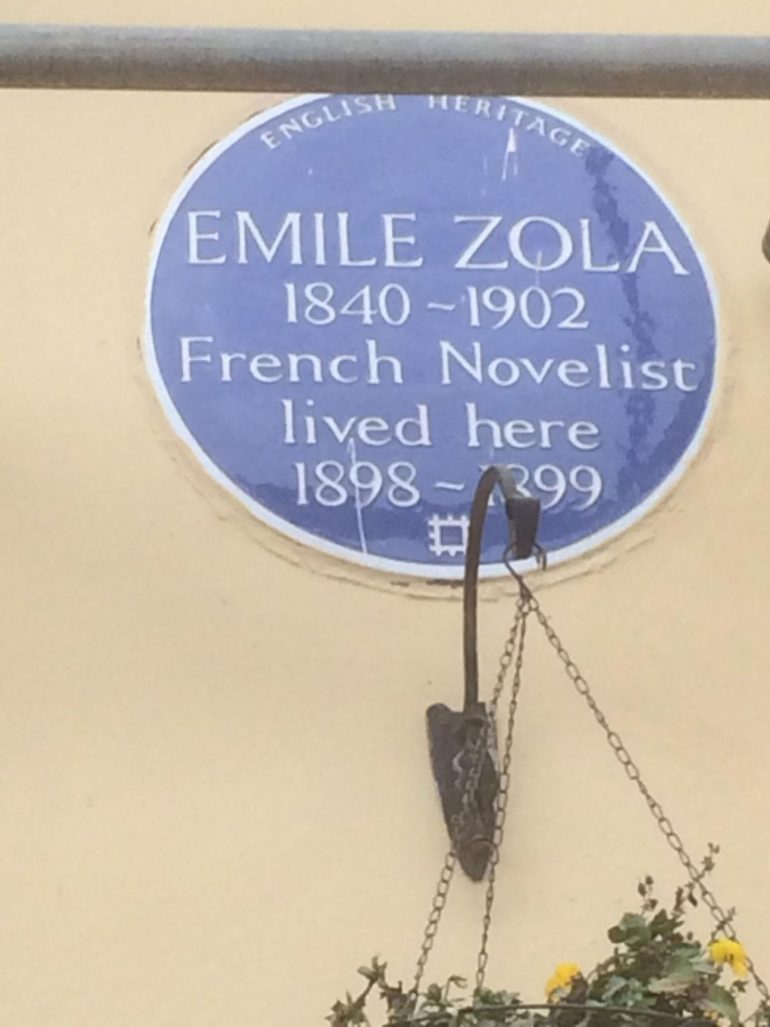

I went there recently to take some photographs and was glad to see that there was a blue plaque to remember him, even if it was obscured by scaffolding as the hotel has a facelift.

Queen’s Hotel in Norwood part of London where French novelist lived in exile. Photo Credit: © Edwin Lerner.

The cause of Zola’s flight from his native France was the notorious Dreyfus affair. A French army officer Alfred Dreyfus was sentenced to life imprisonment on Devil’s Island for passing secrets to Germany.

Another officer Georges Picquart produced evidence which showed that the real culprit was Ferdinand Esterhazy but, as Dreyfus was Jewish, anti-Semitism won the day.

It was Zola who was sentenced to a year in prison and stripped of his Legion d’Honneur for attacking the military establishment in the famous article ‘J’Accuse!’ Rather than going to prison Zola fled to London and spent nearly a year here before returning to his native France.

While in South London Émile Zola wrote most of the book Fecundite and a short story Angeline inspired by a local tale which he transposed to France. He received visits from friends and supporters as well as both his wife and mistress.

Queen’s Hotel in Norwood area of London: Blue Plaque for Emile Zola.

Zola had a complicated love life but remained loyal to both the wife Alexandrine, who was childless, and mistress Jeanne, with whom he had two children.

He indulged in his hobby of photography and gradually became familiar with the language although he could never abide our cooking. (A Frenchman criticising English cooking? Incroyable!)

Eventually Dreyfus’s innocence became obvious to all but the most intransigent and Zola returned to France where he was pardoned. He was, however, not fully exonerated until 1906 four years after his death from carbon monoxide poisoning.

The jury is out on whether his death was an accident or murder but in 1953 the French newspaper Liberation published an account of a death-bed confession which claimed that the chimney to his house had been blocked by an anti-Dreyfusard who was working on the roof at the time.

Émile Zola may well have paid with his life for defending an innocent man.

Read Michael Rosen’s book “The Disappearance of Emile Zola” for more on Zola In London and Robert Harris’s novel “An Officer and a Spy” for the story of Picquart’s role in the Dreyfus affair.

Leave a Reply