St Paul’s Cathedral is one of London’s most instantly recognisable landmarks. The unmistakable Dome and the beautiful west towers dominate the skyline of the City. Designed by one of our greatest architects, Sir Christopher Wren, and completed in 1711, St. Paul’s Cathedral is London’s cathedral and embodies the spiritual life of British people. This article contains ten lesser-known highlights to look out for on a visit to the cathedral, giving you a real ‘insider’s visit.’ To unravel more secrets of St. Paul’s Cathedral, book a full tour with a London Blue Badge Tourist Guide.

St Paul’s Cathedral – As viewed from Ludgate Hill. Photo Credit: ©Visit London Images.

St Paul’s Cathedral – As viewed from Ludgate Hill. Photo Credit: ©Visit London Images.

1. Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee memorial marker

Before you go up the great West Front steps to enter the Cathedral, look down at the memorial inscription which reads, “Here Queen Victoria returned, thanks to Almighty God, for the sixtieth anniversary of her accession…” On 22 June 1897, Queen Victoria’s National Service of Thanksgiving was held outside St. Paul’s Cathedral at the foot of the west steps. She was very frail by this point in her reign and could not manage to easily climb out of her carriage. So the clergy of St. Paul’s Cathedral brought her special service outside to her! Victoria remained in her carriage throughout the ceremony, surrounded by dignitaries and troops from around the Empire. The day was extremely popular with the people of Britain, demonstrated by the 25,000 specially erected seats along the six-mile processional route. Our current Queen Elizabeth II attended a National Service of Thanksgiving at St Paul’s Cathedral on the final day of her own Diamond Jubilee celebrations in June 2012.

2. The Fire Watch Memorial

At the west end of the nave of St. Paul’s Cathedral, there is a large, white, diamond-shaped tile in the floor which remembers the volunteers of the ‘St Paul’s Watch’ – a team who were responsible for defending the cathedral from aerial attack during the Second World War. The fact that St Paul’s famously survived the onslaught of the Blitz – the German bombing campaign of 1940 and 1941 – is well documented, but the cathedral was actually hit several times. The biggest risk was from ‘incendiary bombs’ which could cause huge fire damage if they took hold in the Dome, and that’s what the Watch were predominantly looking out for. Their duties were to monitor and put out any fires that may start as a result of the bombs that were being dropped during the air raids, keeping detailed logs of nightly activity. Thanks to their dedication, Winston Churchill’s wish that “St Paul’s must be protected at all costs” was achieved.

St Paul’s Cathedral – View of the Dome ceiling. Photo credit: ©Graham Lacdao, St Paul’s Cathedral.

St Paul’s Cathedral – View of the Dome ceiling. Photo credit: ©Graham Lacdao, St Paul’s Cathedral.

3. The painting with ‘celebrity status’

At the end of the north transept is the Chapel of Saints Erkenwald and Ethelburga, where you will find a large painting called ‘The Light of the World’ by Victorian artist William Holman Hunt. It depicts Christ in a dark wood, holding a lantern and knocking at an overgrown door with no handle. It is known as ‘a sermon in a frame’ for its clear and strong spiritual message; the door represents the door of our lives – the gateway to the human soul. A wealthy philanthropist named Charles Booth was a great devotee of Hunt’s work; he organised for the painting to be taken on a ‘world tour’ at the start of the twentieth century, where it was seen by around two million people. Booth then donated the painting to St Paul’s Cathedral in 1907. It is considered so precious that during the Second World War it was ‘evacuated’ to a safe location, and even today sits within a ‘just in case’ fire-proof box!

4. The man who ‘lost America’

In the South Transept of St. Paul’s Cathedral, there is a monument commemorating General Charles Cornwallis, who served as a Governor in the British Army in both Ireland and India. He had many victories and was known as a great strategist and reformer, but unfortunately for him, one major loss has coloured his legacy forever. He is more frequently remembered as the commanding officer who surrendered at the Siege of Yorktown, Virginia, in 1781, ending the final battle of the Revolution and effectively paving the way for the progression of American Independence.

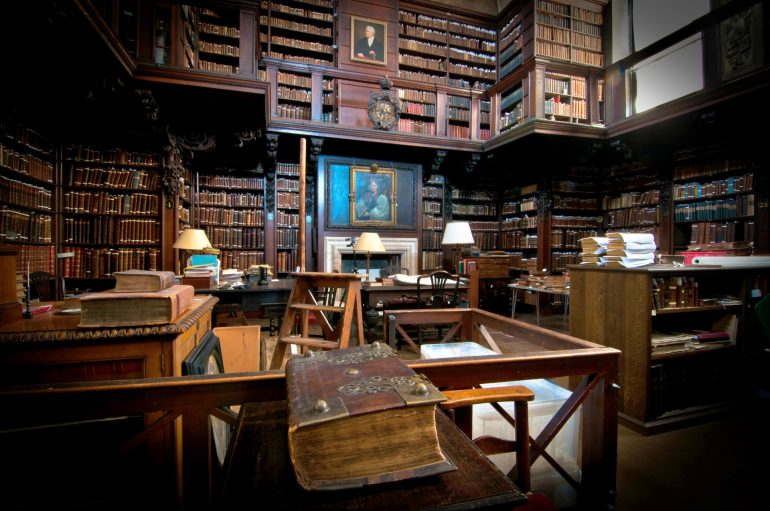

St Paul’s Cathedral – The Library. Photo credit: ©Graham Lacdao, St Paul’s Cathedral.

St Paul’s Cathedral – The Library. Photo credit: ©Graham Lacdao, St Paul’s Cathedral.

5. A sea-sick lion?

Opposite the Cornwallis memorial is a monument to another very famous British military leader: Admiral Horatio Nelson. Lord Nelson was one of our greatest ever naval captains and led the British fleet of warships against the French during the Napoleonic Wars of the early 1800s. The sculptor, John Flaxman, chose to depict a lion at Nelson’s feet – the lion traditionally represents British pride, bravery, and might. Yet many think that this lion looks rather unwell? Nelson apparently suffered from sea-sickness throughout his naval career, and perhaps this is Flaxman’s nod to Nelson’s humanity – sculpting a symbol that normally represents strength and power looking a little under the weather!

6. The effigy of John Donne

In the South Quire Aisle of St. Paul’s Cathedral, you will find an unusual memorial: a tall statue of a man wrapped in a ghostly shroud. This monument honours a great British writer and cleric – the seventeenth-century poet and preacher John Donne. As well as an admired writer (“…no man is an island…”) he was also Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral for the last ten years of his life, hence his prominent memorial here. Two things to note about his effigy sculpture: first, that it is believed to be an accurate rendering of him; he supposedly posed wearing a shroud in the weeks before he died! The other interesting point is hinted at by the scorch marks on the marble urn at the bottom of the sculpture, and the dates that he was Dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral – between 1621 and 1631. Those of you familiar with the Great Fire of London will know that the date of that great disaster was 1666 – so this memorial survived the Great Fire and was salvaged intact from the charred remains of the previous Old St Paul’s Cathedral!

St Paul’s Cathedral – Nelson’s Chamber restored. Photo credit: ©Graham Lacdao, St Paul’s Cathedral.

St Paul’s Cathedral – Nelson’s Chamber restored. Photo credit: ©Graham Lacdao, St Paul’s Cathedral.

7. A hidden space rocket

At the eastern end of St. Paul’s Cathedral is the peaceful space of the American Memorial Chapel. This was consecrated in 1958 and commemorates the 28,000 American servicemen who lost their lives in the Second World War whilst serving in British or Canadian formations. All of the intricate limewood carving in the chapel depicts emblems and symbols of the United States and includes native plants, flowers and birds. Look very closely at the final panel above the pews before you exit the chapel – hidden amongst the carvings is a delicate and slender space rocket: a tribute to American achievements in space exploration during the late 1950s.

8. The Victorian Mosaics

Queen Victoria once famously complained that St Paul’s Cathedral was “dull, dingy and undevotional”. The response to this remark was the mosaics that now decorate the ceiling and walls of the quire – the most sacred area at the heart of the cathedral where the choir, clergy, and worshippers sit for the daily Evensong service. Installed between 1896 and 1904, to a design by William Blake Richmond, the ceiling illustrates the song of Creation from the Old Testament, whilst the wall mosaics tell the story of the Angel Gabriel visiting Mary with the news that she will give birth to Jesus. We can never know what Wren would have thought about the vibrant additions to his original Baroque design, but the glittering mosaics are certainly a spectacular sight.

St Paul’s Cathedral – OBE Chapel. Photo credit: ©Graham Lacdao, St Paul’s Cathedral.

St Paul’s Cathedral – OBE Chapel. Photo credit: ©Graham Lacdao, St Paul’s Cathedral.

9. Christopher Wren’s resting place

Down in the Crypt of St Paul’s Cathedral, the atmosphere is more hushed, and some of Britain’s most celebrated 18th and 19th-century artists, craftsmen, and military leaders are buried within. The great architect of St Paul’s itself is also buried here – look for a simple black stone slab that marks the final resting place of Sir Christopher Wren. You might be surprised that there is no elaborate effigy or stone monument to his memory – after all, Wren was responsible for the rebuilding of fifty-one churches following the Great Fire of London, as well as St Paul’s Cathedral, much of the current layout of Maritime Greenwich, and large parts of Hampton Court and Kensington Palaces. The influence he had on the London skyline and on other architects he trained or mentored cannot be underestimated. The poignant plaque above his grave explains why no great memorial sculpture is needed; the last line of the Latin inscription reads, “Reader if you seek his monument, look around you…”

10. Nelson’s ‘second hand’ sarcophagus

Two of Britain’s greatest army and naval heroes were buried here at St Paul’s Cathedral, following grand state funerals. Arthur Wellesley, the first Duke of Wellington, lies beneath an immense marble and granite tomb at the centre of the Crypt, and a short distance from him is the resting place of a man we met earlier on our visit – Admiral Horatio Nelson. At the top of Nelson’s tomb is a shiny, black marble sarcophagus, which remarkably is one of the oldest items in the cathedral – it was made in the 1520s! It was originally commissioned by Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, a famous Lord Chancellor of King Henry VIII, but following the disgrace and dismissal of Wolsey (over his failure to secure Henry’s first marriage annulment) the sarcophagus was never used. It was kept at Windsor Castle, and nearly 300 years later was presented to the Admiralty by King George III as a fitting gift to honour Lord Nelson. There is also another great story to do with Nelson involving the transportation of his body back to England and a barrel of finest brandy, but we will save that one for the live tour… ☺

St Paul’s Cathedral – Geometric staircase. Photo credit: ©Peter Smith, St Paul’s Cathedral.

St Paul’s Cathedral – Geometric staircase. Photo credit: ©Peter Smith, St Paul’s Cathedral.

St Paul’s Cathedral is open to visitors for sightseeing and services from Monday to Saturday, and on Sundays just for services. This article has only scratched the surface of some of the wonderful secrets and treasures of St Paul’s Cathedral so if you would like to know more, a tour with a Blue Badge Tourist Guide is an entertaining and easy option. We look forward to welcoming you to London!

Leave a Reply