On the afternoon of 7th September 1940, 350 German bomber planes attacked London, devastating the docks area and killing over 400 people. The day became known as Black Saturday and marked the beginning of a bombing campaign – the Blitz – that terrorised the city for eight months. Around 20,000 Londoners were killed. Eighty years on from Black Saturday, Blue Badge Tourist Guide Ruth Polling explores how remnants of that period can still be seen in London today.

The Bombing:

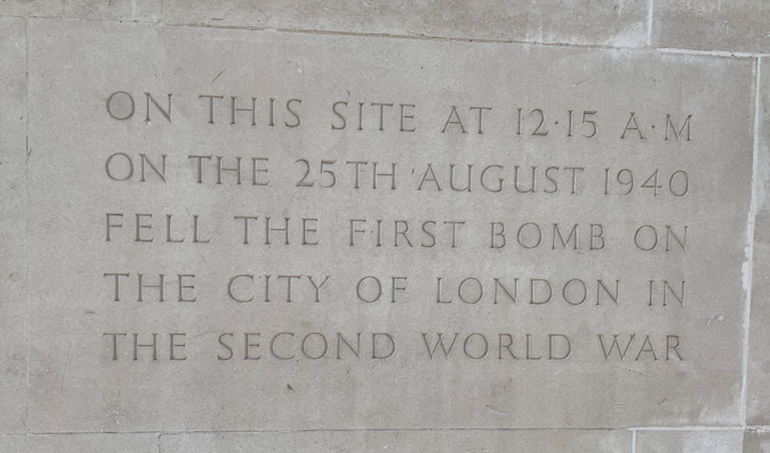

The bombs that fell on the 7th of September weren’t the first to hit London during the Second World War. Throughout the summer, the German air force – the Luftwaffe – had been attacking Britain with the aim of destroying the Royal Air Force (RAF) and launching an invasion. During a period known as the Battle of Britain, the Germans struck airbases, and shipping and industrial targets. The first bomb to hit the very centre of London fell in Fore Street on the night of the 24/25th August, possibly by mistake.

Plaque on Fore Street identifying the site of the first WW2 bomb in the centre of London. Photo Credit: © Ruth Polling.

Plaque on Fore Street identifying the site of the first WW2 bomb in the centre of London. Photo Credit: © Ruth Polling.

In retaliation, the British bombed Berlin. The failure of the Luftwaffe to destroy the RAF and the attacks on Berlin led the Germans to change tactics. They switched from targeting airfields to bombing London, with the first major raid on the 7th of September.

The Blitz had begun.

After the initial afternoon attack, the bombers returned to London that evening and every evening for 57 nights. It was the most intense period of bombing suffered by any British city during the war. Other towns – centres of industry and ports – were attacked from November. Raids continued on London, although they were no longer nightly. In total London suffered 71 major raids in eight months. One of the most devastating was on the night of the 10/11th May 1941, killing 1,436 Londoners and causing fires to burn across the city, including at the Houses of Parliament. This was the last raid of the Blitz.

In May 1941, the Germans redeployed their planes in preparation for the invasion of the Soviet Union. While a small number of “hit and run” raids took place between 1941 and 1943, London wasn’t to see another bombing campaign until 1944.

Seeking Shelter:

The Government and Londoners had expected the capital would be bombed once war broke out. London had been bombed during the First World War, and as technology improved throughout the 1920s and 1930s, governments across Europe made civil defence plans. Britain passed the Air Raid Precautions Act in 1937, requiring local authorities to plan for air attacks.

Much focus was on the provision of shelters for ordinary Londoners. These varied considerably across the city depending in part on the type of housing in the area. In the suburbs, Anderson Shelters that could be partially buried in back gardens were distributed. In poorer areas without gardens, street shelters, and trench shelters in parks were constructed so local communities could seek safety together. In areas of the centre with older houses, many basements were converted into shelters. White-painted shelter signs directed people to them, a few of which can still be seen on houses in the Westminster area.

White-painted shelter sign in the Westminster area. Photo Credit: © Ruth Polling.

White-painted shelter sign in the Westminster area. Photo Credit: © Ruth Polling.

Initially, the government refused to allow people to use the London Underground for shelter out of concern it would disrupt travel. They also feared that having gone deep underground, Londoners would be reluctant to return to the surface after raids. This posed a particular challenge in the poorer area of east London, which had no Anderson or basement shelters. In defiance of the ban, many residents bought tickets for travel and then stayed underground. By mid-September, the government realised it couldn’t prevent this, and at the peak over 150,000 Londoners used underground stations as shelters. Eventually, bunks, toilets, and even entertainment were provided in these areas of the Tube.

Even so, a significant number of Londoners – up to 60% by some estimates – chose not to use any shelters and instead stayed in their houses during raids, hoping for the best.

Remembering Lives Lost:

The saddest reminders of the devastation caused by the Blitz on London are those that recall the ordinary people killed fighting fires, or sheltering underground or at home. An estimated 43,000 British civilians lost their lives, and it is thought that around half of them were in London. Most local authority cemeteries have memorials to those killed in 1940/41.

More shocking, though, is the huge number of plaques and memorials marking places where people were killed. You can come across them when you least expect to be reminded of the war – on the sides of houses, under railway lines, and in London parks. Some were constructed shortly after the war, but most are more recent.

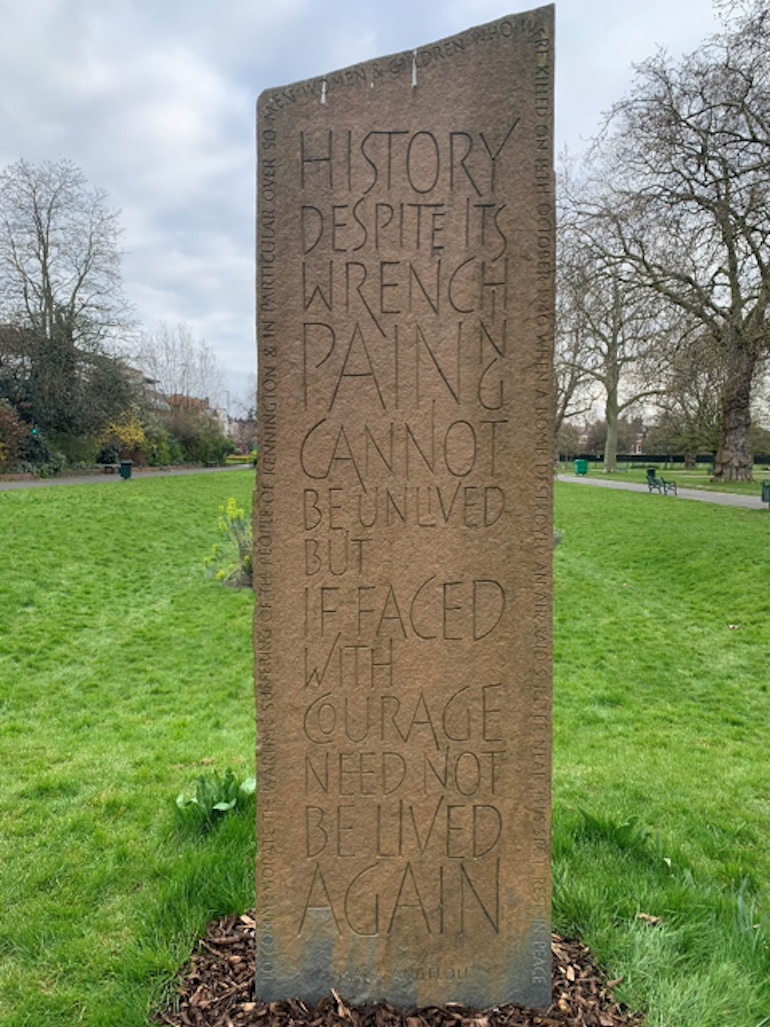

In 2006 a memorial was unveiled to those who lost their lives when a single bomb caused a trench shelter to collapse in Kennington Park on the evening of 15th October 1940. At the time, the government didn’t publish specific details of bombing incidents, so it is impossible to know the exact number of fatalities, but it is thought to be over 100. Only 48 bodies were ever recovered, and the damaged trench was filled in a month later, leaving the remaining victims buried under the park where they died.

WW2 memorial in Kennington Park. Photo Credit: © Ruth Polling.

WW2 memorial in Kennington Park. Photo Credit: © Ruth Polling.

Those that are known are also remembered in the Civilian War Dead 1939 – 1945 Roll of Honour, located close to the West Door of Westminster Abbey. The original seven volumes list 66,375 fatalities from the Blitz and later bombing campaigns on Britain during World War II. The Roll of Honour provides names as well as details including where each person lived and died, reminding us that each one was an individual to be remembered.

Bomb Sites:

You can also still find bomb-damaged buildings across London – another type of memorial. If you look carefully, you can see the scars of blasts. A good example is the north side of the Church of St. Clement Danes at Aldwych, where the damage was preserved when the church was rebuilt for the Royal Air Force in the 1950s.

Just a five-minute walk from St. Paul’s Cathedral, the destruction is much more obvious. Christchurch Greyfriars was a 13th-century church rebuilt after the Great Fire of London in 1666 and then gutted on 29th December 1940 during one of the most famous raids of the Blitz. The whole area around St. Paul’s was flattened by incendiary bombs, and the night became known as the Second Great Fire of London. At least seven historic churches were heavily damaged, and only the efforts of the volunteer firewatchers at St. Paul’s saved the cathedral itself.

After the war, it was decided not to rebuild Christchurch Greyfriars, and to preserve the surviving tower and north wall as a memorial. The population of central London had been declining for over a century by this time as people moved to the new suburbs, so the congregations of these historic churches had dwindled.

A public park was created in the footprint of the church in 1989, with climbing plants where the pillars would have been and planting in the place of pews. It is a lovely, peaceful place where office workers come to eat their lunch, perhaps unaware this is a bombsite.

Christchurch Greyfriars. Photo Credit: © Ruth Polling.

Christchurch Greyfriars. Photo Credit: © Ruth Polling.

Rebuilding the City:

Of course, not all bomb sites could be preserved as gardens. Some of London’s most famous historic buildings were severely damaged during the Blitz, but this is often forgotten because of the amazing rebuilding and restoration work that took place after the war.

An example is the east end of St. Paul’s Cathedral, restored to create the beautiful American Memorial Chapel remembering U.S. servicemen who lost their lives while based in Britain. It was opened in 1958 and can be visited today.

The debating chamber of the House of Commons, often seen in coverage of the British Parliament on television, looks historic but in fact, was opened in 1950. It replaced the chamber destroyed on the night of 10/11th May 1941. Only the entrance archway to the chamber reveals the story – still made of the broken masonry of its predecessor.

Even more urgent was the need to rehouse Londoners after the war. A million homes were destroyed or damaged, and there was huge pressure to rebuild them. This combined with slum clearance in the worst-affected districts – particularly the East End – led to the complete rebuilding of whole areas that today are still dominated by housing from the 1950s and 1960s.

In some areas, only a few houses were obliterated. Those that merely suffered some damage were patched up and reoccupied while those destroyed were rebuilt and not always in the same style. It is a common sight across London today to see a row of 19th-century housing interrupted by a small number of post-war residences in the middle – a legacy of the pattern of bombing in residential areas.

Example of intermittent postwar housing in London. Photo Credit: © Ruth Polling.

Example of intermittent postwar housing in London. Photo Credit: © Ruth Polling.

To learn more about the Second World War in London, a visit to the Imperial War Museum is highly recommended. The Museum has an amazing collection, including Turning Points – its Second World War Gallery.

Imperial War Museum. Photo Credit: © Ruth Polling.

Imperial War Museum. Photo Credit: © Ruth Polling.

Eighty years on, there are reminders of the Blitz right across London if you know where to look. Little-noticed plaques, new houses in the middle of older terraces, and parks created in the aftermath of the war. They remind us of the suffering endured – the cost to the city and its people. Look out for them when you are next in London.

Leave a Reply